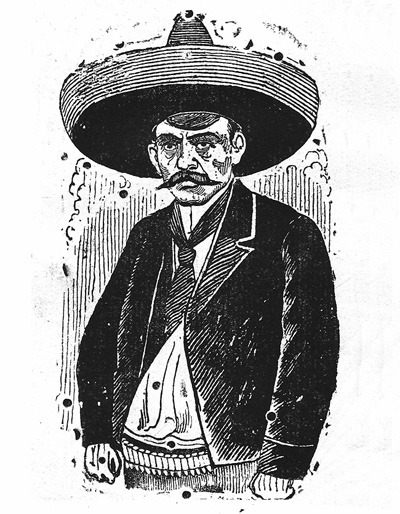

José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913) was a Mexican lithographer, engraver, and printmaker whose work captured the humor, struggles, and beliefs of everyday people during a time of political change.

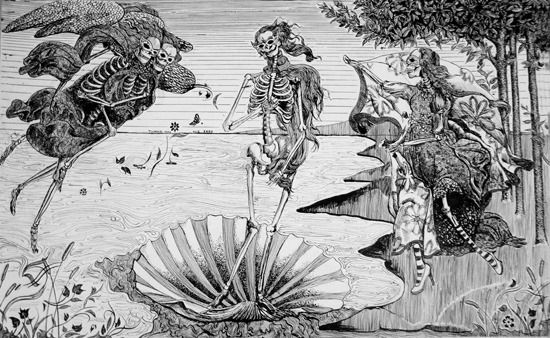

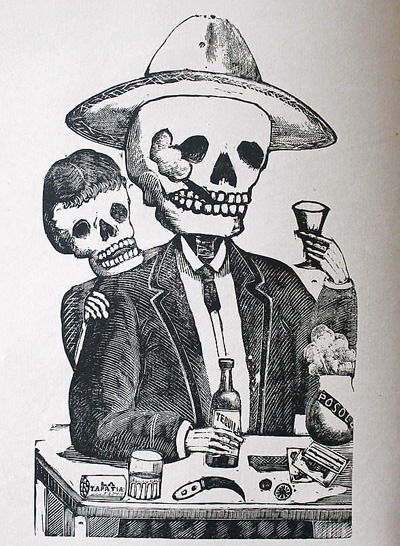

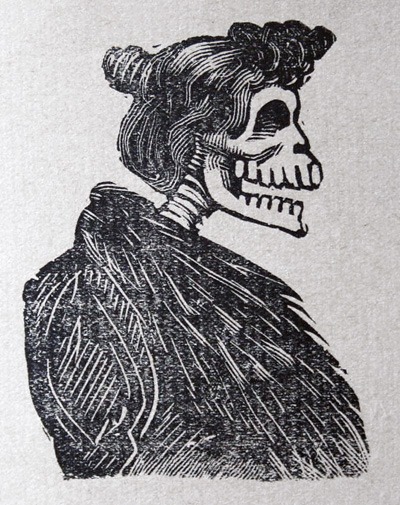

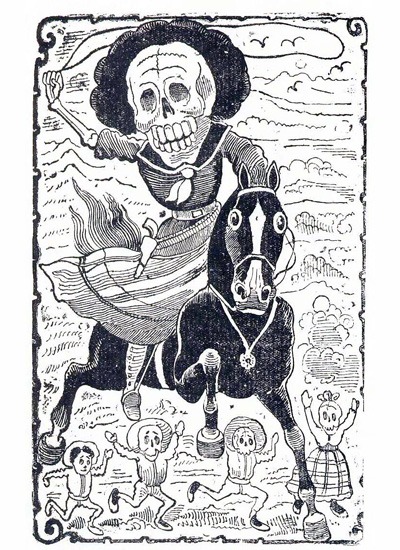

He is best known as the creator of La Calavera Garbancera, later renamed La Catrina, now an iconic figure of Day of the Dead celebrations and Mexican folk art.

Scholars and artists alike consider Posada the precursor of Mexican modern art.

Early Life and Education

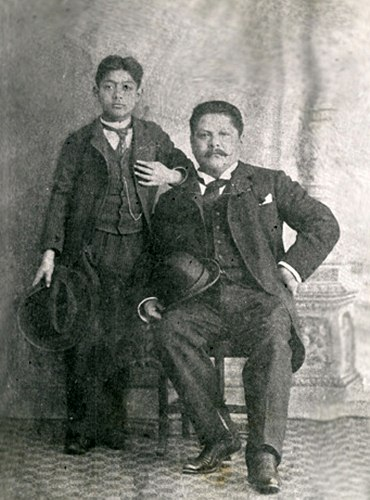

Posada was born on February 2, 1852, in Aguascalientes, Mexico, to Petra Aguilar and Germán Posada, a baker. His family was humble and largely illiterate, but his artistic talent was evident from a young age.

He received his first lessons from his older brother José Cirilo Posada, a schoolteacher, who encouraged him to draw while working as a classroom assistant. Posada’s gift for illustration led him to study briefly at the Academy of Fine Arts of Aguascalientes, where he began refining his technique.

First Steps as an Illustrator

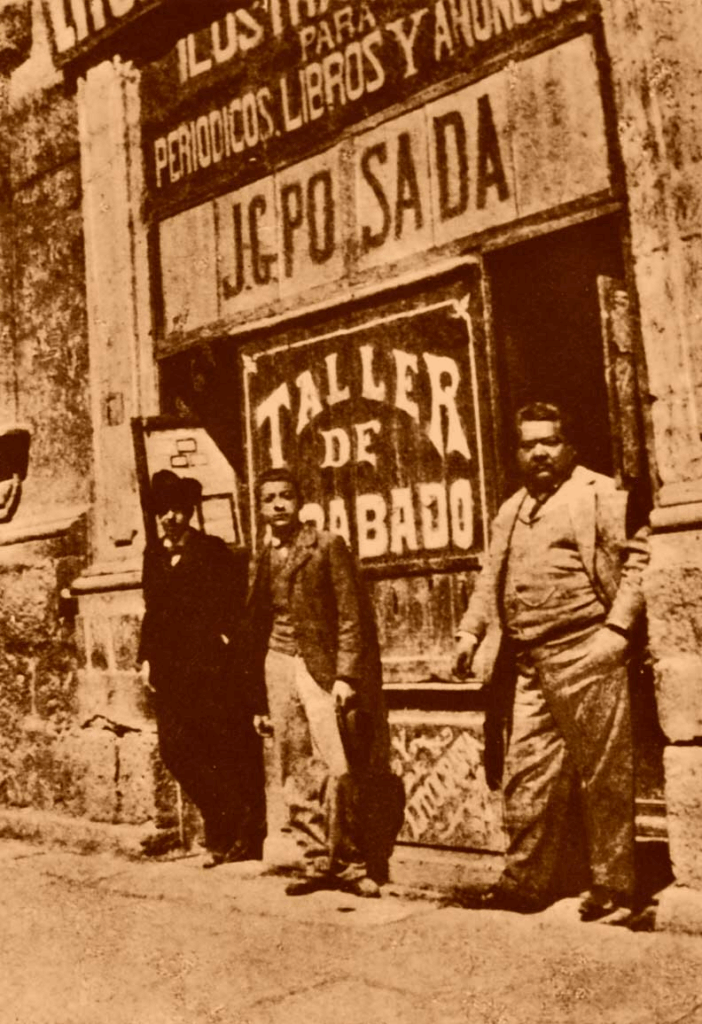

In 1868, at only sixteen, Posada began working at the printing house of José Trinidad Pedroza, one of the best presses in the region. Pedroza became both mentor and friend, teaching him lithography and engraving on wood and metal.

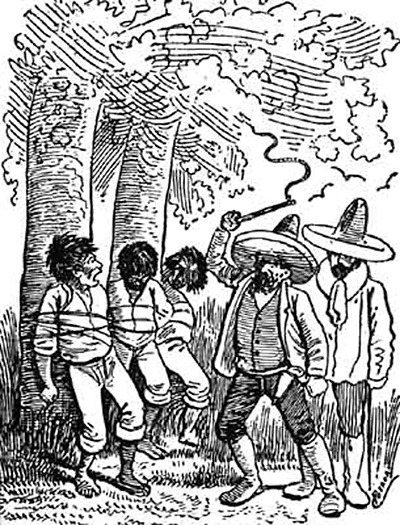

By 1871, at age nineteen, Posada was already the head cartoonist of the satirical newspaper El Jicote (The Wasp), which often criticized local politicians. The publication’s success and controversy helped shape Posada’s lifelong style: sharp, direct, and socially conscious.

A few years later, Pedroza and Posada opened a second printing shop in León, Guanajuato, where Posada married María de Jesús Vela in 1875. The couple had one child who died young.

Posada built a reputation as a skilled illustrator, creating images for newspapers, books, and commercial packaging such as matchboxes and cigarette labels.

In 1888, a devastating flood destroyed much of León, prompting Posada and his wife to relocate to Mexico City, where he would produce his most influential work.

Life and Work in Mexico City

Upon arriving in the capital, Posada began contributing illustrations to newspapers like La Juventud Literaria (The Literary Youth), where editor Ireneo Paz—grandfather of poet Octavio Paz—praised his imagination and predicted a great future for him.

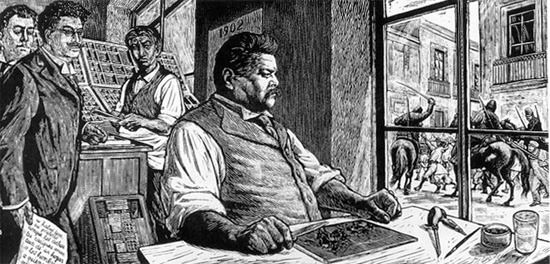

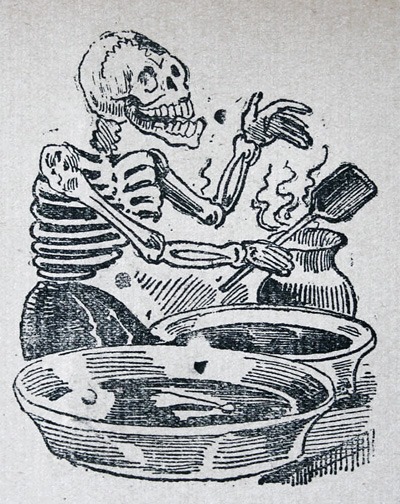

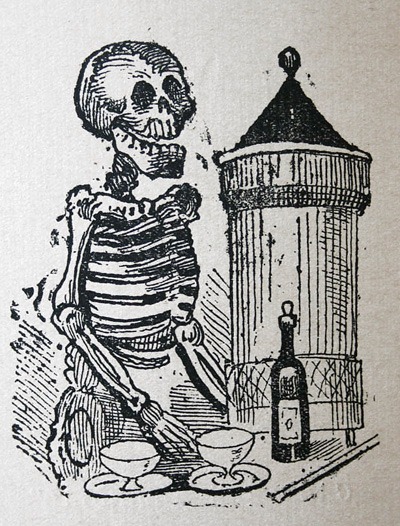

Posada soon opened a modest workshop, producing engravings for songbooks, religious prints, news sheets, recipe pamphlets, and board games. In a city where most people could not read, his images became a vital form of visual storytelling.

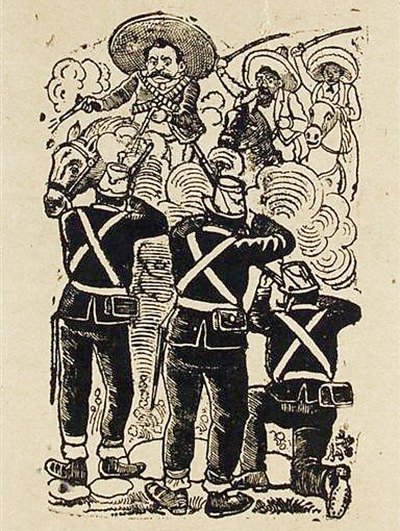

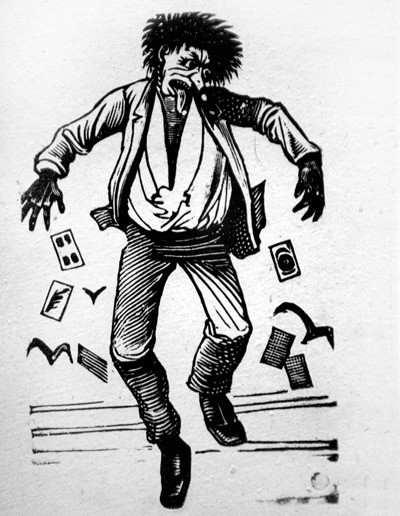

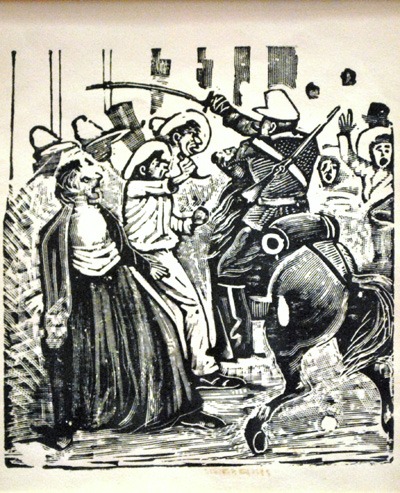

Around 1890, he began working for the publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, whose print shop became the center of Mexico’s illustrated popular press. Posada’s productivity exploded—he created thousands of engravings depicting politics, daily life, disasters, crimes, miracles, and folktales.

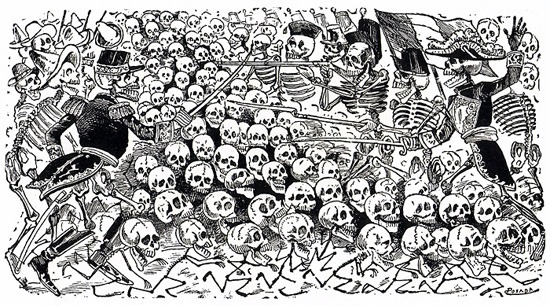

Working alongside engraver Manuel Manilla, Posada perfected a distinctive technique using relief etching on zinc plates, which allowed for fine detail and tonal shading.

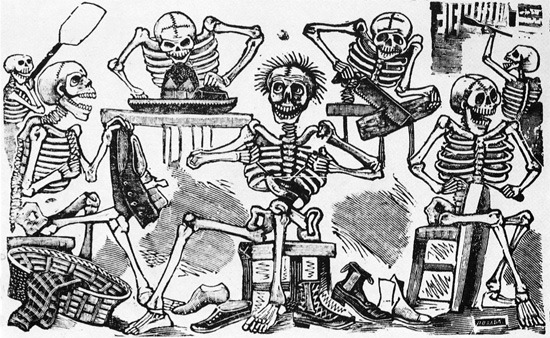

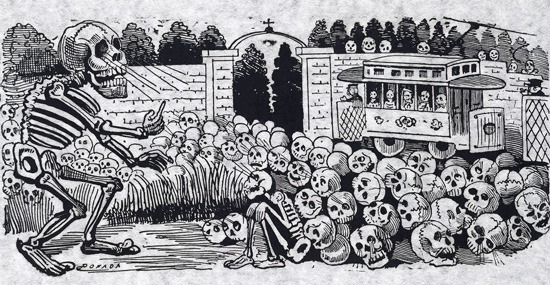

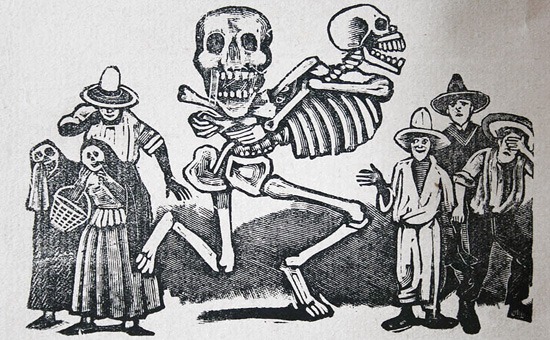

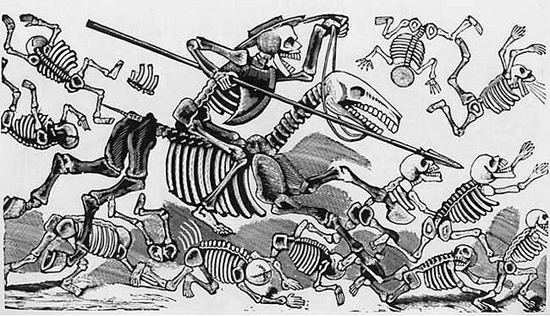

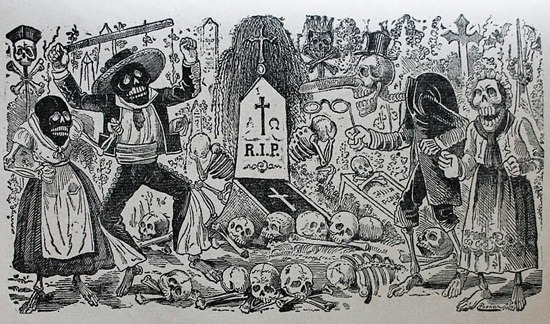

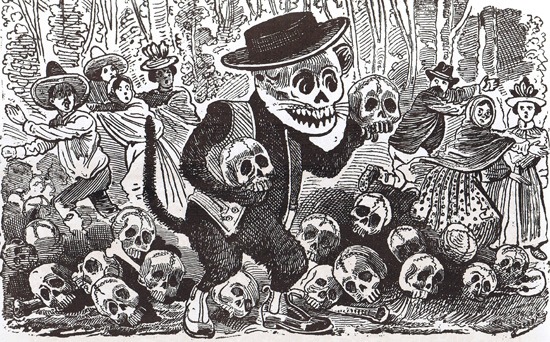

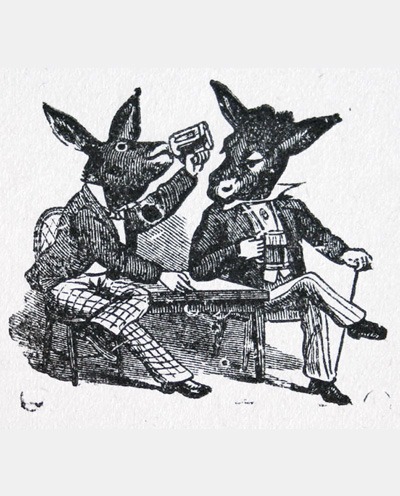

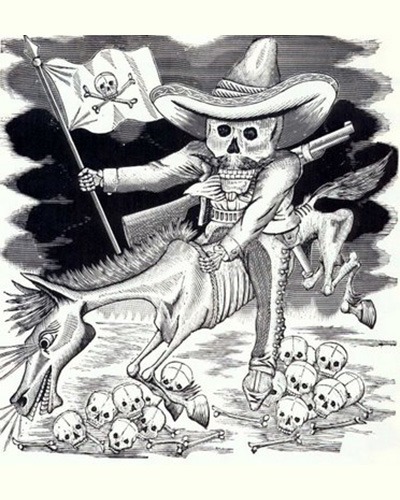

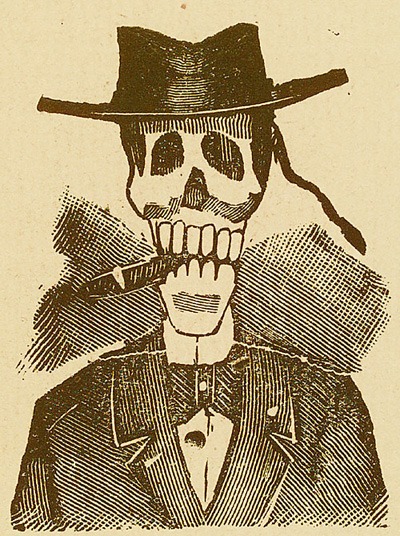

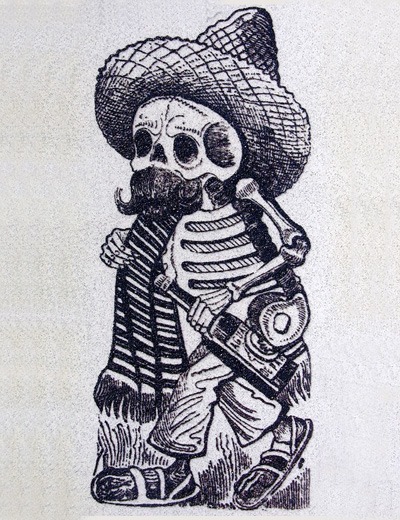

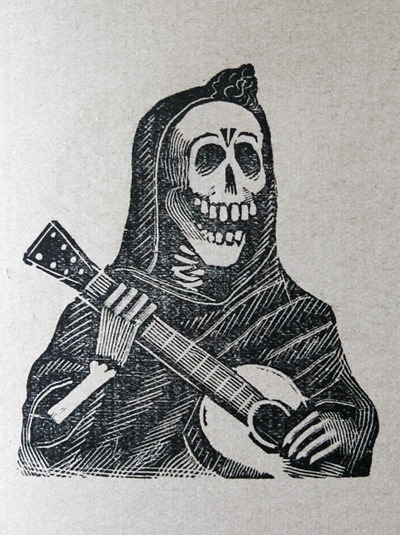

Together with Vanegas Arroyo and poet Constancio Suárez, Posada produced the calaveras literarias: short satirical poems about public figures, accompanied by his humorous skeleton illustrations.

It was in these prints that he created La Calavera Garbancera, mocking the vanity of those who denied their Indigenous heritage while trying to appear European. This image would later evolve, through Diego Rivera, into La Catrina—the elegant Lady of Death now celebrated across the world.

Themes and Artistic Legacy

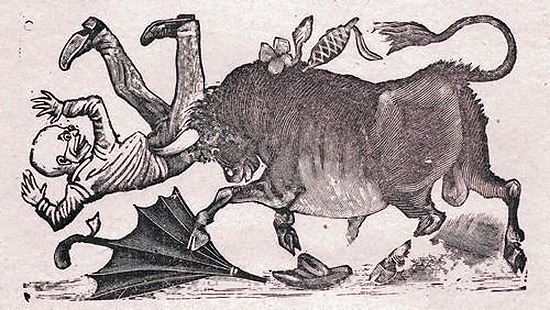

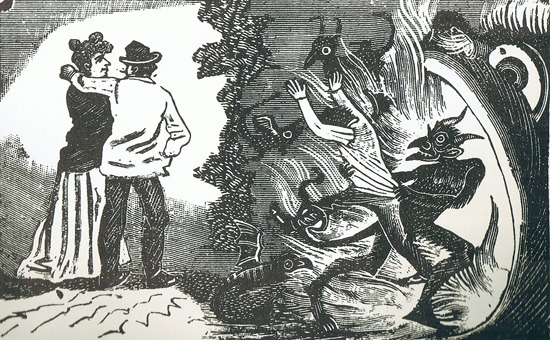

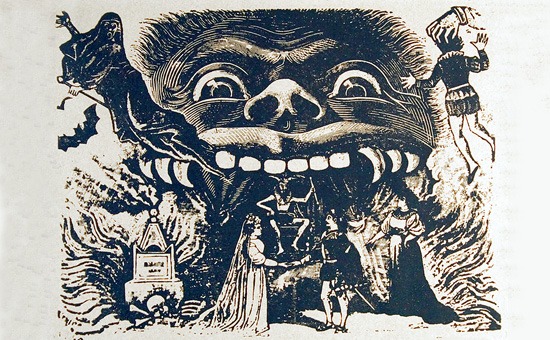

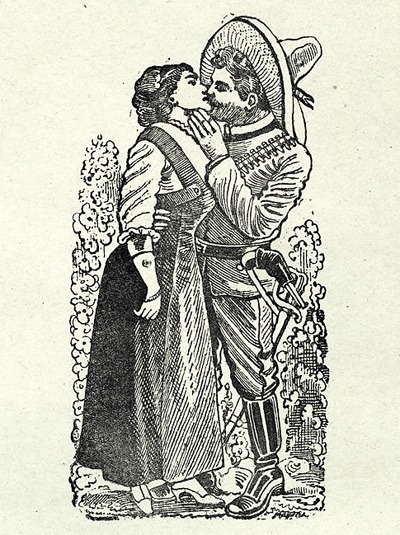

Posada’s art combined humor, social critique, and folklore. He illustrated:

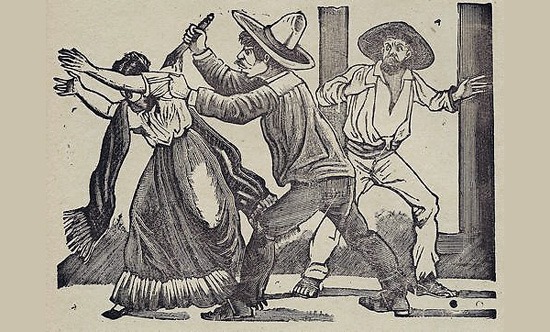

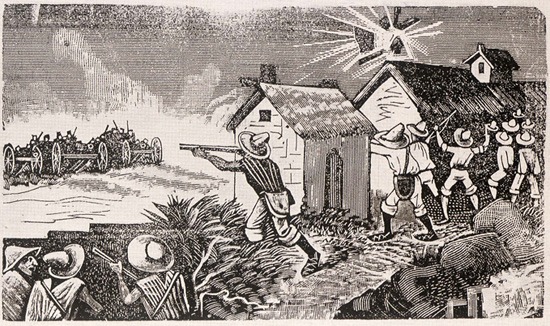

- Political corruption and class inequality

- Natural disasters and sensational crimes

- Religious visions, miracles, and ghost stories

- Daily life and urban scenes of ordinary people

He worked tirelessly and left behind an estimated 15,000 engravings over his lifetime.

His art spoke directly to Mexico’s working class, reflecting their fears, joys, and beliefs at the turn of the century.

Posada died in Mexico City on January 20, 1913, a widower and without children. He was buried in a common grave at the Panteón de Dolores, his work largely forgotten until later rediscovered by the next generation of Mexican artists.

Posada’s Influence on Mexican Modern Art

Decades after his death, Posada’s work was recognized as a cornerstone of modern Mexican identity.

Artists, writers, and historians have celebrated him as both popular and universal.

- Diego Rivera considered him his artistic father and placed Posada at the center of his mural “Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central”, holding hands with La Catrina.

- José Clemente Orozco said that watching Posada work inspired him to become an artist.

- Octavio Paz, Nobel Prize–winning poet, wrote that Posada achieved “a minimum of lines and a maximum of expression,” calling him an expressionist who never took himself too seriously.

- Luis Seoane, painter and engraver, described Posada as “the greatest engraver in the Americas, deeply Mexican and therefore profoundly universal.”

- Historian Fernando Gamboa emphasized his deep connection to the people, calling him “a popular artist in the deepest and highest sense of the word.”

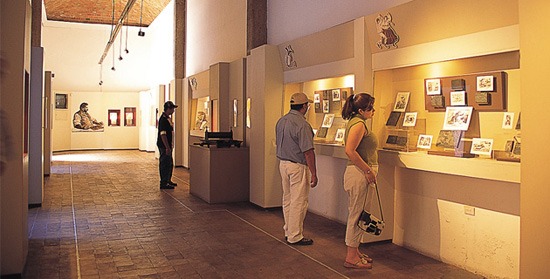

The José Guadalupe Posada Museum

Posada’s hometown of Aguascalientes honors his memory through the Museo José Guadalupe Posada, located in the Jardín de San Marcos.

The museum houses hundreds of his original prints, plates, and historical documents, alongside contemporary works inspired by his style.

Each year, exhibitions and workshops celebrate his contribution to Mexican art and his enduring influence on La Catrina and the calavera tradition.

Conclusion

José Guadalupe Posada transformed everyday life into timeless art.

Through his engravings, he gave a visual voice to Mexico’s people and captured their humor, faith, and resilience during times of change.

His legacy endures not only in museums and murals but also in the living traditions of Day of the Dead, La Catrina, and Mexican folk art around the world.

Leave a Reply