The Day of the Dead altars, known in Mexico as altares de muertos or ofrendas, are the heart of the Día de Muertos celebration.

On November 1 and 2, families across Mexico build these altars in their homes, schools, cemeteries, and plazas to welcome the souls of departed loved ones back to the world of the living.

According to ancient belief, during these two nights the spirits can cross the threshold between life and death, guided by the scent of flowers, the glow of candles, and the offerings lovingly prepared for them.

Altars are both a devotional act and a work of art, blending Indigenous, Catholic, and folk traditions into one of Mexico’s most meaningful rituals.

The Meaning of the Altar

Each altar serves as a symbolic gateway that connects both worlds.

It tells the spirits they are remembered, loved, and still part of the family.

Altars for children (angelitos) are prepared on the evening of October 31, decorated with white flowers such as nube (baby’s breath) and alhelí (hoary stock), representing purity.

Offerings include sweet tamales, hot chocolate, atole, fruit, candies, and toys—everything suitable for a child’s joy.

On the night of November 1, families replace or eat the children’s offerings and prepare for the arrival of adult souls.

Altars are then filled with marigolds, spicy foods, mezcal, cigarettes, and the favorite dishes of the departed, turning remembrance into celebration.

Structure of the Altar

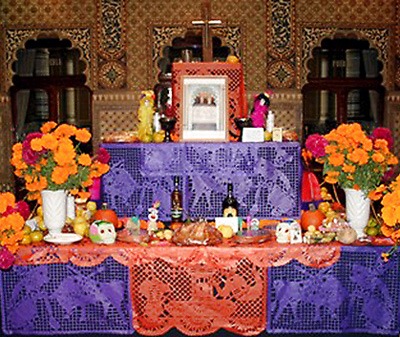

Altars vary by region and family tradition. They can be modest or elaborate, but most share common elements and layers of symbolic meaning.

Levels

- Two levels represent heaven and earth.

- Three levels stand for heaven, purgatory, and earth.

- Seven levels—common in rural Mexico—symbolize the seven stages souls must pass to reach peace.

The Arch

Placed at the top of the altar, it represents the entrance to the world of the dead.

In some regions it is made from cempasúchil (marigold) flowers, and in others from reed or sugarcane.

It marks the point where the spirit passes to join the family once more.

Essential Elements of the Altar

Though details change from region to region, these elements are found on most altars across Mexico:

Photograph

A photo of the honored person gives the altar the purpose of making the loved one present again through memory and image.

Flowers

Flowers symbolize life and the fragility of existence.

The cempasúchil, or flor de muerto, is the most iconic: its bright orange petals are laid on the floor to form a path from the door to the altar, guiding the souls home with color and scent.

Other flowers like baby’s breath or amaranth are added according to region and meaning.

Papel Picado

Colorful cut-paper flags hang across the altar and represent the element of air. Their gentle movement mirrors the invisible presence of the souls and the joy of reunion.

Pan de Muerto (Bread of the Dead)

This sweet, anise-scented bread is a communal offering.

Its round shape symbolizes the circle of life, while the bone-shaped decorations honor those who came before us.

Each region has its own variation—some topped with sugar, sesame, or even small figurines.

Sugar Skulls and Candies

Skulls made of sugar, chocolate, or amaranth seeds remind us of death’s omnipresence, yet they are decorated with vibrant colors, turning death into celebration.

For children’s altars, alfeñique candies shaped like animals, fruits, or angels are added as playful gifts.

Food and Drinks

Each family prepares the favorite dishes of their departed loved ones.

Common offerings include tamales, turkey with mole, pumpkin in brown sugar syrup (calabaza en tacha), seasonal fruits, and atole.

Adult altars may include mezcal, pulque, tequila, or even a cigarette pack which are tokens of pleasure to welcome the spirits home.

Candles

Candles represent light, faith, and hope, illuminating the way for souls.

Some regions light one candle per spirit; others place four to represent the cardinal directions.

The flickering flame transforms the altar into a sacred space.

Water

A glass of water refreshes the soul after its long journey. It is also a symbol of purity and renewal.

Salt

A small dish of salt purifies and prevents the soul from corruption during its brief visit among the living.

Copal (Incense)

Burning copal resin purifies the environment and attracts souls with its sweet smoke, a practice inherited from pre-Hispanic rituals.

Petate (Mat)

A woven palm-leaf mat is placed beside the altar for the spirits to rest.

It recalls the Indigenous belief that souls need comfort after traveling between worlds.

Personal Belongings

Objects such as a favorite hat, toy, instrument, or work tool personalize the offering, making the returning soul feel at home.

Religious Icons

Crosses, images of the Virgin Mary, or patron saints blend Catholic devotion with ancestral remembrance.

Regional Variations

Altars reflect the diversity of Mexico’s geography and traditions:

- In Michoacán, altars are covered in bright marigolds and reeds shaped into arches.

- In Oaxaca, intricate papel picado and handmade clay figures decorate multi-level displays.

- In Yucatán, altars, called hanal pixán, feature local foods like mucbipollo (buried tamale) and traditional beverages.

- In Puebla, the focus is often on symmetry and floral crosses made with cempasúchil and gladiolus.

Every region carries the same message: to remember is to keep alive.

The Celebration of Reunion

After November 2, families gather to share the food and drinks that were offered to the dead.

It is said that the souls only absorb the essence of the offerings, leaving behind their flavor for the living to enjoy.

This final meal symbolizes unity between both worlds—a joyful communion of memory, love, and gratitude.

Conclusion

The altar of the dead is more than decoration; it is a dialogue between life and death, a living artwork that carries centuries of devotion and creativity.

Through flowers, paper, food, and light, families reaffirm that love transcends time.

Each ofrenda, whether simple or grand, tells the same story:

that to honor our dead is to celebrate life itself.

Leave a Reply