In the fertile valley of southern Puebla lies Izúcar de Matamoros, cradle of one of Mexico’s most celebrated folk art traditions, the multicolored clay sculptures.

This pottery style is famous for its vibrant hues and intricate decoration that resembles painted filigree. The best-known creations include the Tree of Life, candelabra, incense burners, and whimsical Day of the Dead figures filled with humor and devotion.

These pieces are not only decorative; they are narratives in clay, telling stories of faith, fertility, and community passed down through generations.

A Historical Legacy

Izúcar de Matamoros, known in pre-Hispanic times as Itzoacan (“place of the flint”), was once an important Mixtec city under Aztec rule, connected by multiple trade routes.

When the Spaniards arrived, the town was granted as an encomienda to Pedro de Alvarado in 1521. The Dominican friars began evangelizing soon after, establishing the Church and Monastery of Santo Domingo de Guzmán in 1552, completed in 1612.

Religious life flourished with the founding of the Brotherhood of the Blessed Sacrament in 1652, which organized elaborate ceremonies involving processions, incense, and offerings.

The town’s potters began crafting incense burners and candelabra for these rituals, gradually transforming utilitarian objects into works of art.

Traditionally, multicolored clay candelabra were given to newlyweds as a blessing to ensure many children and fertile harvests. The incense burners, still used today in brotherhood ceremonies, are central to a 350-year-old tradition: a sacred silver platter symbolizing the host is passed between the town’s fourteen neighborhoods each year. Each transfer is marked by a mass, incense purification, and communal meal, sustained entirely by donations and faith.

The Evolution of the Craft

While Izúcar’s clay tradition dates back centuries, its most recognizable style which is vibrant, intricate, symbolic and emerged in the 20th century, shaped by visionary artisans who turned everyday pottery into fine folk sculpture.

Aurelio Flores (1901–1987): The Father of Multicolored Clay

Born in the neighborhood of Santa Catarina Contla, Aurelio Flores grew up in a family of potters. From a young age, he helped his parents make candelabra and incense burners for church ceremonies. Over time, he developed a new sculptural form: the Tree of Life, depicting Adam, Eve, the Serpent, and the Archangel Gabriel amid a forest of leaves, flowers, and birds.

Aurelio worked in his fields by day and sculpted by night, also serving as a healer and musician. His art began to attract merchants from Puebla City, and soon his pieces were known throughout Mexico.

He is remembered as the first to elevate Izúcar’s pottery from devotional craft to collectible art.

His son Francisco Flores Sánchez continued his legacy, maintaining the same style and values: craftsmanship, simplicity, and faith. Francisco also inherited his father’s love for farming and mariachi music, working the land until his passing in 2006.

The Castillo Family: A Dynasty of Color and Imagination

The next great chapter in Izúcar’s pottery history began in the 1960s with the Castillo family from the neighborhood of San Martín Huaquechula.

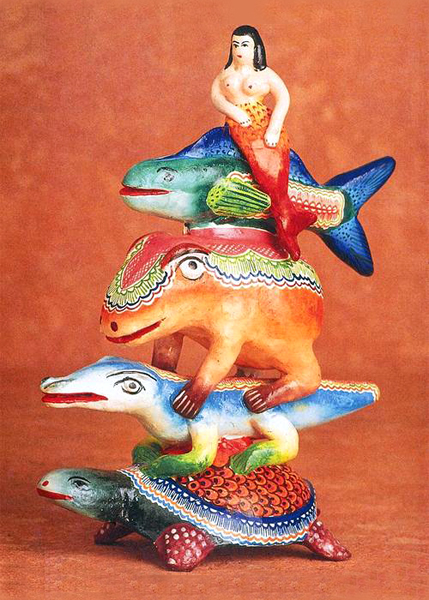

Founded by Catalina Orta Urosa, who revived her parents’ dormant pottery skills, the family developed a new aesthetic marked by bold color, fine linework, and fantastical subjects, from saints and mermaids to skeletal musicians and Frida Kahlo figures.

Catalina taught her six children, four of whom became master artisans:

Heriberto Castillo Orta

Heriberto specialized in mermaids, trees of life, and candlesticks painted with aged golden backgrounds and vibrant colors. His pieces reflect a blend of myth and luminosity.

Agustín Castillo Orta

Though less known, Agustín produced beautiful pieces faithful to the family style, balanced, detailed, and richly ornamented.

Isabel Castillo Orta

Renowned for her delicate brushwork, Isabel has exhibited and taught across the United States. Her pieces which often portray the Virgin of Guadalupe, Day of the Dead, and Tree of Life embody grace and precision.

Her workshop now includes her children and grandchildren. Among them, Gregorio and Giovanni Mercado Morgan are emerging artists continuing the family legacy, while their mother Virginia Morgan Tepetla crafts her own trees of life and catrinas.

Alfonso Castillo Orta (1944–2009)

The most celebrated of them all, Alfonso Castillo Orta brought Izúcar’s clay to international recognition.

Honored as a Master of Mexican Folk Art by the Banamex Foundation and winner of the 1996 National Prize of Folk Art, Alfonso was a master sculptor and painter. His works have been exhibited in museums across Mexico, the United States, Canada, and Europe.

His wife Martha Hernández and their children: Verónica, Alfonso, Marco, Martha, and Patricia Castillo Hernández continue his legacy through their own workshops, preserving both the style and the spirit of his work.

Pictured above: Frida Kahlo Candelabra by Alfonso Castillo Orta.

Casa Balbuena and Arte CasBal

María Luisa Balbuena Palacios, once married to Heriberto Castillo Orta, co-founded the workshop Itzoacán. After their separation, she established Casa Balbuena, creating a wide range of pieces, from monumental Trees of Life to miniature animal candleholders.

Her sons Jorge and Ulises Castillo Balbuena founded their own workshop, Arte CasBal, in 2004, blending traditional motifs with contemporary design. Their pieces are known for their vivid palettes and storytelling detail, continuing the artistic lineage of both parents.

Tomás Hernández Báez

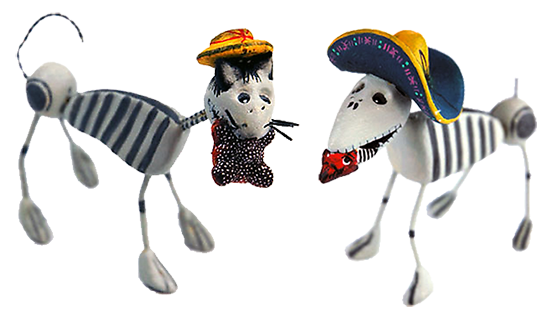

Brother to Martha Hernández (wife of Alfonso Castillo), Tomás Hernández Báez began as an apprentice in their workshop and later established his own. His work, known for its refined sculpting and intricate painting, often focuses on Day of the Dead scenes where cats, dogs, and skeleton musicians are brought to life through color and movement.

How Multicolored Clay Is Made

The making of a multicolored clay sculpture is a meticulous process that can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks, depending on the size and complexity.

1. Preparing the Clay:

The raw clay arrives in solid clods, which are crushed with a mallet, sifted, and soaked in water to soften. After resting for a week, it is kneaded until it reaches the consistency of dough and divided into balls weighing about 8 pounds each.

2. Shaping the Sculpture:

Most pieces are hand-coiled, though small elements like leaves or flowers may be formed in molds. Once sculpted, the figures are left to dry — a process that can take hours or days.

3. Firing:

The dry pieces are fired in a kiln at around 850°C (1,560°F) for six hours, then cooled slowly over sixteen hours.

4. Base Painting and Decoration:

The cooled sculptures are polished and painted with white acrylic, which prepares the surface for decoration

Each artisan then applies bright acrylic paints using delicate brushes to create the detailed linework and motifs that define the Izúcar style. Once painted, the piece is coated in furniture varnish to protect the colors and give it a glossy finish.

The result is a masterpiece of patience and imagination, a sculpture that bursts with color, meaning, and movement.

A Living Tradition

The multicolored clay of Izúcar de Matamoros represents more than artistry; it is a living history of faith, family, and creativity.

Each generation has added its own chapter, from Aurelio Flores’s biblical Trees of Life to Alfonso Castillo’s playful catrinas and modern icons.Today, workshops across Izúcar continue to thrive, their walls lined with drying clay figures that will soon dance with color. These artisans, rooted in centuries-old tradition yet open to new inspiration, keep proving that Mexican folk art is as alive and evolving as the culture it celebrates.

Leave a Reply