La quema de Judas, or Judas Burning, is a lively Easter-time tradition celebrated in Mexico on Sábado de Gloria (Holy Saturday).

Large papier-mâché effigies of Judas Iscariot—stuffed with fireworks—are ignited and exploded in public plazas, symbolizing the destruction of betrayal and evil.

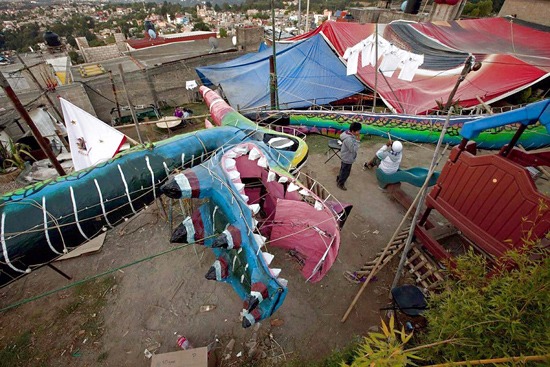

The spectacle mixes faith, satire, and folk art, filling the streets with noise, color, and laughter as crowds gather to watch towering figures—sometimes five meters high—burst into flames.

Smaller Judas figures, about 30 centimeters tall, are also sold for home celebrations.

Origins of the Celebration

The burning of Judas has roots in European Christian rituals dating back to medieval times.

Across Spain, Portugal, and Greece, people burned effigies of Judas Iscariot during Easter to symbolize repentance and the triumph of good over evil.

Spanish and Portuguese colonizers carried the custom to the Americas, where it took hold in Mexico, Brazil, Venezuela, Ecuador, Uruguay, Chile, and the Philippines.

In Mexico, the earliest Judas figures were made of straw and rags and simply burned.

With the arrival of paper and fireworks through the Manila–Acapulco trade route, the effigies evolved: artisans began crafting cardboard figures stuffed with cohetes (firecrackers), which would explode dramatically when lit.

From Religion to Satire

After Mexico’s War of Independence, the Judas burning gradually lost its purely religious meaning and became a secular community event.

Effigies began to represent not only Judas Iscariot but also public figures accused of corruption or betrayal. Shop owners sponsored burnings by stuffing Judas figures with candies, bread, or cigarettes to attract customers.

By the mid-19th century, the effigies often took the shape of devils or caricatures of unpopular politicians.

A law passed in 1849 prohibited dressing or naming Judas figures to resemble specific individuals—a reminder of how politically charged the tradition had become.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, La quema de Judas was a nationwide event.

In Mexico City, artisans sold hundreds of effigies in public markets during Holy Week.

One of them was Pedro Linares, the legendary cartonero who later invented alebrijes.

In the 1950s, Linares’s workshop in La Merced employed over 300 helpers just to meet demand for Judas figures.

The Decline and Revival

Over time, censorship, safety regulations, and urban restrictions on fireworks led to a decline in public burnings.

However, artisans and local governments have helped preserve the tradition by organizing community events and sponsored burnings.

In Mexico City, the Linares family continues to build and burn Judas figures in La Merced.

In Santa Rosa Xochiac, an entire neighborhood participates in making massive Judas effigies that are paraded and ignited in the town plaza, blending ancient ritual with local pride.

The modern Judas has become a canvas for creativity—some shaped like alebrijes, others like politicians or devils—celebrating art as much as satire.

Symbolism and Meaning

For many scholars, the Judas burning functions as a scapegoating ritual, a collective way to release social tension.

Others see it as an act of purification—burning away corruption, betrayal, and evil to restore balance.

Through laughter and spectacle, it allows people to confront betrayal and hypocrisy while reaffirming community bonds.

In Mexican culture, where death and humor intertwine, La quema de Judas embodies the same spirit as Day of the Dead celebrations: facing the darker side of life through art and festivity.

Judas Figures as Folk Art

By the end of the Revolution, traditional Judas effigies were commonly depicted as red-horned devils, made by cartoneros (papier-mâché artisans) and sold in markets before Holy Week.

Over time, the craft grew more elaborate and expressive, largely thanks to two outstanding artists: Carmen Caballero Sevilla and Pedro Linares.

Carmen Caballero Sevilla

Carmen Caballero devoted her life to making Judas figures and skeletal sculptures.

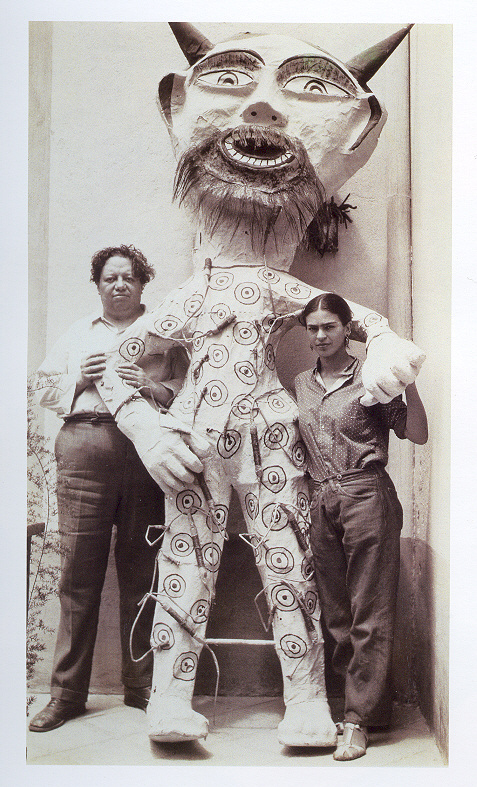

She caught the attention of Diego Rivera, who met her while painting the murals at the Abelardo Rodríguez Market.

Rivera admired her artistry so much that he invited her to work in his studio, where she created Judas, skeletons, and charros for him.

Her pieces appeared in Rivera’s painting The Painter’s Studio and were later collected by Frida Kahlo, Rufino Tamayo, and even Henry Moore.

Though her name faded over time, sculptor and curator Enriqueta Landgrave helped revive interest in her work, which now survives in the Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Dolores Olmedo museums.

Pedro Linares and the Modern Judas

Before becoming famous for his alebrijes, Pedro Linares was one of Mexico City’s most important Judas makers.

He produced hundreds of traditional devil effigies each year, then expanded the craft to include skeletons and hybrid creatures, combining elements of fantasy and satire.

Even after his international recognition for alebrijes, Linares continued burning Judas figures in his neighborhood, seeing it as an essential cultural act.

His descendants—especially Miguel Linares and Paula Linares—still carry on the tradition, creating large-scale Judas sculptures that blend humor, political commentary, and imagination.

Where to See Judas Burnings Today

- La Merced Market (Mexico City): annual Judas burning organized by the Linares family.

- Santa Rosa Xochiac (Mexico City): neighborhood celebration featuring giant Judas effigies.

- Museo de Arte Popular (Mexico City): exhibitions on cartonería and traditional papier-mâché figures.

- Various towns in Estado de México and Puebla: local artisans continue building and burning Judas during Holy Week.

Conclusion

The Judas Burning tradition unites Mexico’s history of faith, satire, and artistic invention.

Born from colonial ritual and transformed by folk imagination, it has become a vivid expression of resistance and renewal.

Through the hands of artisans like Carmen Caballero and Pedro Linares, the Judas effigy turned from a symbol of betrayal into a masterpiece of popular art—proof that in Mexico, even fire and laughter can keep heritage alive.

Leave a Reply