Papel picado—literally “perforated paper”—is the traditional Mexican art of cutting intricate designs into tissue paper to create colorful banners.

These delicate flags decorate Day of the Dead altars, streets, and homes during festivals, weddings, and national holidays. Each design reflects the occasion it honors, from skulls and saints to doves, angels, or national emblems.

The art of papel picado captures the spirit of celebration: fleeting, vibrant, and full of meaning.

Origins and History

The roots of papel picado trace back to pre-Hispanic paper-making traditions. Indigenous peoples of central Mexico made amatl—a bark-based textile—from fig or mulberry trees.

The Aztecs used this paper for codices, ritual decorations, and offerings to the gods, sometimes coating it with rubber and pigment.

Modern artisans from Guerrero still use this material, known as amate paper, as a canvas for traditional Nahua paintings.

However, unlike common belief, papel picado did not evolve directly from amate.

Amate is fibrous and cannot be finely cut without tearing. The true origins of papel picado emerged much later, shaped by colonial trade and local creativity.

The Birthplace: San Salvador Huixcolotla, Puebla

The town of San Salvador Huixcolotla, in the state of Puebla, is recognized as the cradle of papel picado.

Its name in Nahuatl means “place of abundant thorns.” Originally inhabited by Nahua and Popoloca peoples, the town was established by Spanish settlers in 1539 and grew near large haciendas.

During the colonial period, Puebla was on the trade route that carried goods from the Philippines through Acapulco to Veracruz and then to Spain. Among the imported items was a thin, brightly colored silk paper known as papel de China (China paper).

Locals began crafting decorations from this material, and by the 1920s, artisans in Huixcolotla were producing cut-paper banners for markets and festivals.

By the 1970s, papel picado had become a staple across central Mexico, used to adorn Day of the Dead altars, Independence Day parades, and Christmas celebrations.

Mexican migrants later carried the tradition abroad, spreading it across the Americas and beyond.

How Papel Picado Is Made

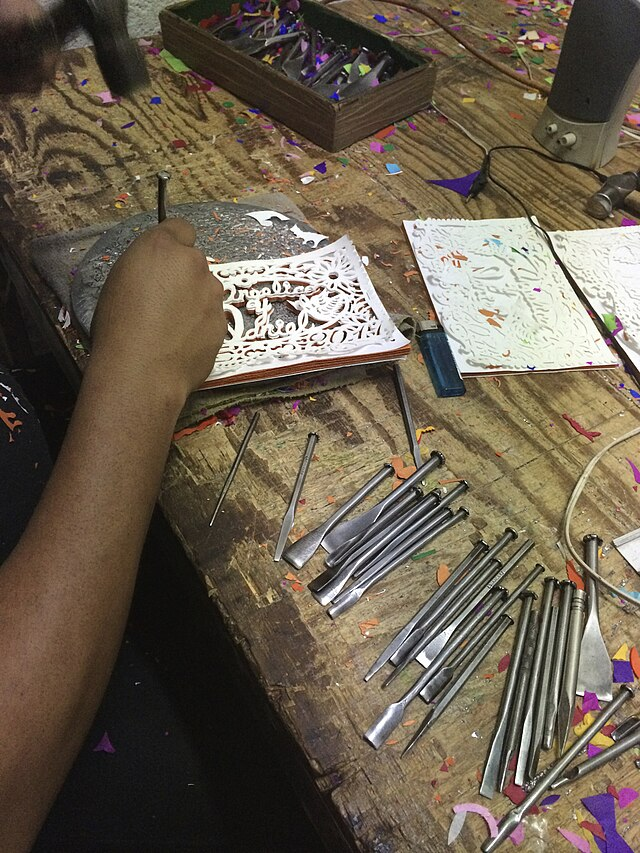

Traditional papel picado is cut by hand using stacks of delicate tissue paper placed over a lead plate as a base.

A manila-paper stencil is laid on top, and artisans use small chisels and hammers to cut through dozens of sheets at once, forming repeated patterns.

Steps of the Process

- Designing the pattern: drawn on manila paper.

- Stacking: layers of tissue paper are placed over the lead sheet.

- Chiseling: dozens of cuts made with fine chisels of various shapes.

- Assembly: sheets are glued or sewn to a string to form long banners.

Each workshop keeps its own pattern archives, often passed down through generations.

While many artisans still use traditional tissue paper, some now work with plastic film, which resists weather and lasts longer outdoors.

However, mass-produced die-cut plastic banners have begun replacing handcrafted ones, putting this centuries-old technique at risk.

In 1998, the state of Puebla declared the artisanal papel picado of San Salvador Huixcolotla an official part of its cultural heritage.

Patterns and Symbolism

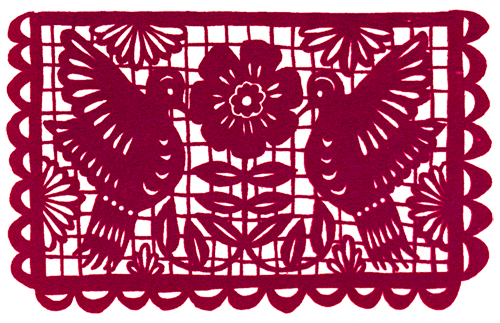

The designs of papel picado are as varied as Mexico’s celebrations:

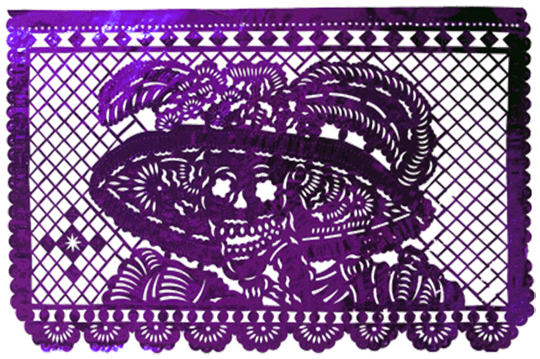

- Day of the Dead (Día de Muertos): skeletons, skulls, and La Catrina, often inspired by José Guadalupe Posada’s engravings.

- Christmas: nativity scenes, angels, bells, and stars.

- Independence Day (September 16): the national emblem, eagles, and heroes of the Revolution, in green, white, and red.

- Religious Festivals: saints, crosses, and floral motifs.

- Personal Celebrations: birthdays, weddings, and baptisms, often with names or custom designs.

The choice of color carries meaning:

- 🟣 Purple and black for mourning and remembrance.

- 🟢 Green, white, and red for patriotism.

- 💛 Yellow and orange for offerings to the dead.

- 🎉 Bright multicolors for joy and community.

An Ephemeral Art

The fragility of papel picado gives it its poetry.

Each banner lasts only as long as the celebration it adorns, a reminder that beauty and joy are as fleeting as paper in the wind.

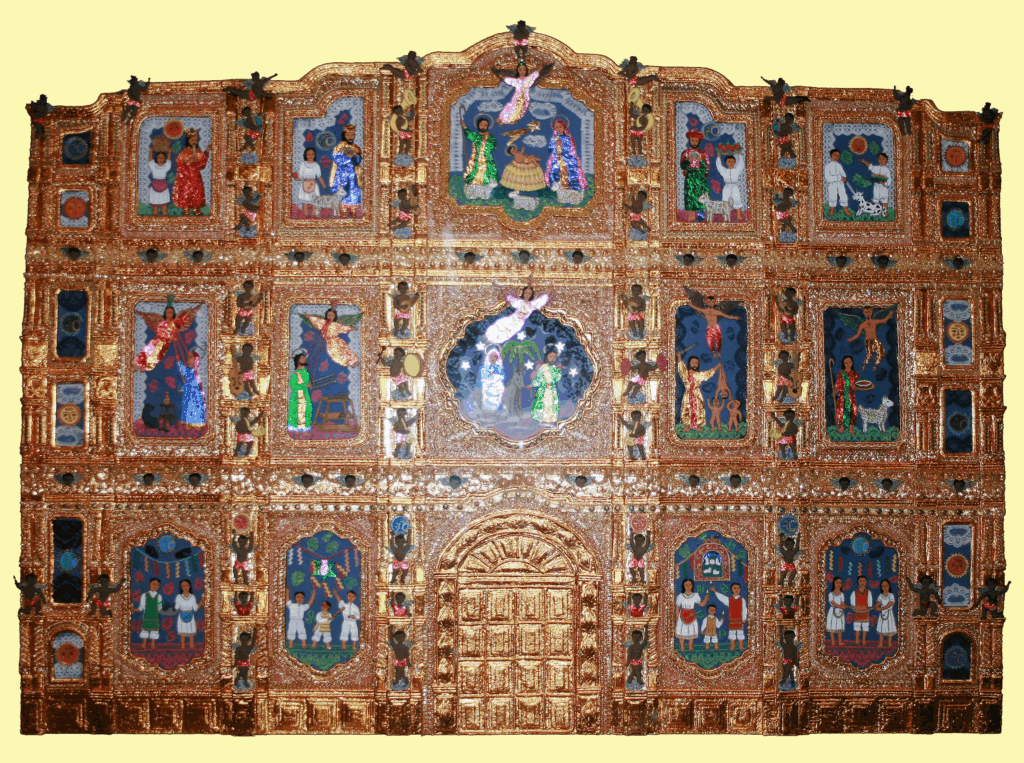

Master artisan Pedro Ortega Lozano, from Tláhuac, Mexico City, has elevated the craft to fine art. Born in 1960 and self-taught, he creates complex compositions using metallic, tissue, and embossed papers.

His retablos and altars depict scenes of daily life and mythology, blending popular art with personal narrative.

Pedro Ortega has received national and international recognition, including the National Folk Art Prize and a feature in the book “Grand Masters of Mexican Folk Art” sponsored by Banamex.

As he once said,

“Just as happiness lasts only a tiny moment, paper is also a tiny moment.”

Where to See Papel Picado

- San Salvador Huixcolotla, Puebla: workshops, local markets, and the annual Feria del Papel Picado.

- Museo de Arte Popular (Mexico City): rotating exhibitions on paper arts and crafts.

- Tláhuac, Mexico City: studio of Pedro Ortega Lozano.

- Day of the Dead Celebrations: across Mexico and Mexican communities abroad, adorning streets, plazas, and altars.

Conclusion

From the colonial trade routes of Puebla to modern altars around the world, papel picado continues to unite history, artistry, and community.

Each cut tells a story of celebration, faith, and transience which are proof that even the most delicate art can endure through generations of hands and hearts.

Leave a Reply