La Catrina is one of the most iconic symbols of Mexican culture.

Elegant, skeletal, and dressed in finery, she represents how Mexico faces death with irony, humor, and acceptance.

Her origins go back more than a century, beginning as a social satire by José Guadalupe Posada and transformed into an enduring emblem through the art of Diego Rivera.

Origins of La Calavera Garbancera

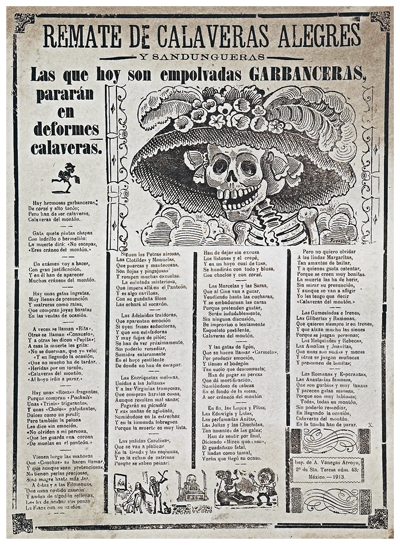

Around 1910, Mexican lithographer and printmaker José Guadalupe Posada created an etching of a female skeleton wearing an extravagant hat decorated with feathers.

The image appeared in a leaflet for calaveras literarias—short satirical verses printed around the Day of the Dead that mocked the living by imagining their death.

Posada titled the illustration “La Calavera Garbancera.”

The word garbancera referred to people of Indigenous heritage who rejected their roots, imitating European fashion and customs instead.

Through this image, Posada criticized the vanity and class pretensions of Mexican society at the end of the Porfiriato era, when the elite often idealized French culture.

Beneath her fine hat, the Garbancera was still a skeleton.

Posada’s message was clear: death makes all people equal, regardless of social status or appearance.

“Those garbanceras who today are coated with makeup will end up as deformed skulls.”

— Traditional saying inspired by Posada’s etching

From Satire to Icon: Diego Rivera and La Catrina

More than three decades later, in 1947, painter Diego Rivera reimagined Posada’s skeleton in his famous mural “Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central” (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda).

Rivera depicted over 400 years of Mexican history, placing La Calavera Garbancera at the center, elegantly dressed and now renamed La Catrina—a term derived from catrín, a slang word meaning “well-dressed gentleman.”

In Rivera’s mural, La Catrina stands arm-in-arm with Posada himself, while young Diego appears holding her hand.

The figure bridges the old and new Mexico, symbolizing the end of the Porfirian era and the beginning of a modern, more egalitarian nation after the Revolution.

Through Rivera’s interpretation, La Catrina became not only a character but a cultural symbol: death personified with grace and dignity.

She reminded Mexicans that death is not to be feared, but faced with style and humor.

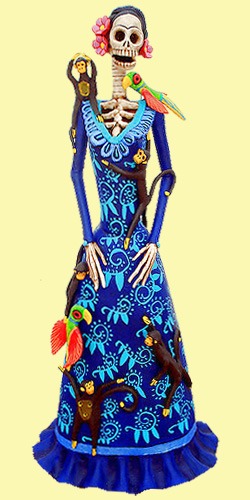

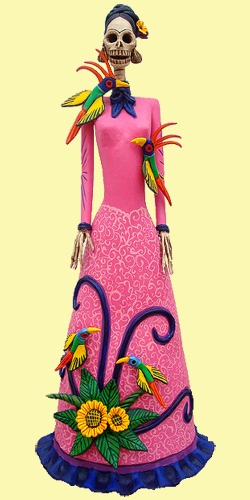

La Catrina in Mexican Folk Art

In 1982, sculptor and painter Juan Torres from Morelia, Michoacán, brought La Catrina into three-dimensional form for the first time, crafting her in clay.

Torres later founded a workshop in Capula, a town with a long pottery tradition dating back to pre-Hispanic times.

Local artisans soon learned and adapted the technique, giving rise to a distinctive Capula Catrina style that has spread to other pottery centers across Mexico.

Today, La Catrina is recreated in nearly every Mexican folk art tradition:

- Papier-Mâché: lightweight and expressive figures often displayed during Day of the Dead festivities.

- Oaxacan Wood Carvings: elegant skeletal ladies painted in bright, symbolic patterns.

- Black Clay (Barro Negro): refined and reflective sculptures from Oaxaca.

- Majolica Pottery: glazed ceramic versions that mix colonial and folk influences.

Each version preserves the essence of Posada’s satire and Rivera’s elegance, turning La Catrina into a bridge between fine art and popular craft.

Symbolism and Meaning

La Catrina is more than a representation of death; she is a reflection of Mexican identity.

She embodies the belief that death is a natural part of life and can be faced with irony and beauty rather than fear.

By dressing death in elegance, Mexicans remind themselves that even the inevitable can be embraced with dignity, color, and laughter.

Her image also critiques vanity and inequality, carrying Posada’s original message that social status and wealth are temporary illusions.

In modern times, she has become a symbol of feminine strength, cultural pride, and resilience.

La Catrina and Popular Culture

La Catrina’s image appears in Day of the Dead parades, altars, and public art across Mexico.

Artists reinterpret her each year through new materials, colors, and regional motifs.

She has also gained international recognition through exhibitions, murals, and film.

The 2017 film Coco introduced global audiences to Mexico’s relationship with death and the afterlife.

Although the film’s skeletal characters are not direct representations of La Catrina, their design and elegance draw clear inspiration from her image, bringing her spirit to a new generation worldwide.

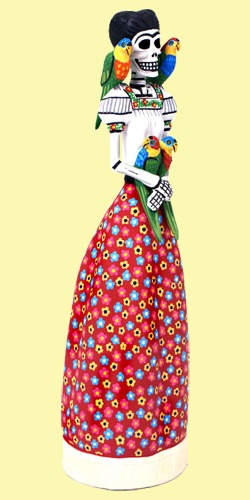

Frida Kahlo and the “Frida Catrina”

In recent years, Mexican folk artists have combined the imagery of Frida Kahlo with La Catrina, creating hybrid figures known as Frida Catrinas.

These sculptures feature the skeletal body of La Catrina with the floral crown, dress, and features inspired by Frida’s self-portraits.

The fusion celebrates both women as icons of Mexican identity and artistic defiance.

Where to See La Catrina

- Museo José Guadalupe Posada (Aguascalientes): dedicated to Posada’s prints and the origins of La Calavera Garbancera.

- Museo Diego Rivera (Guanajuato): showcases Rivera’s murals and drawings, including studies of La Catrina.

- Capula, Michoacán: home of the Feria de la Catrina, a festival celebrating clay Catrina artisans each November.

- Museo de Arte Popular (Mexico City): displays contemporary interpretations of La Catrina in different folk art styles.

Conclusion

From a social satire on class and identity to a timeless symbol of Mexico’s cultural vision of death, La Catrina has evolved through more than a century of art, humor, and tradition.

Created by José Guadalupe Posada, reimagined by Diego Rivera, and reborn by folk artists across Mexico, she continues to remind the world that death, when seen through Mexican eyes, can be as elegant and colorful as life itself.

Leave a Reply