Throughout Mexican history, the mask has served as a bridge between the human and the divine.

From the ceremonial rituals of the ancient Zapotecs and Mayas to the lively dances of modern festivals, masks in Mexico embody transformation, the act of becoming someone, or something, else.

Today, they remain among the most fascinating forms of Mexican folk art, blending spiritual symbolism, performance, and craftsmanship into a single, powerful tradition.

Origins and Evolution

The Earliest Masks

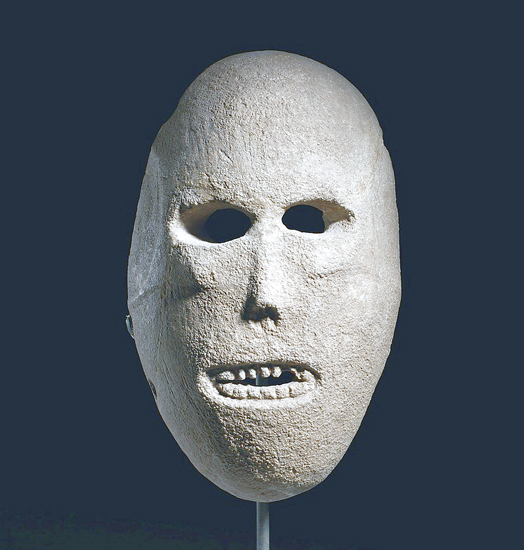

The use of masks in rituals and celebrations is one of humanity’s oldest artistic practices. Globally, the oldest known mask is over 9,000 years old, but Mexico’s own tradition extends back at least 3,000 years, to the great civilizations of Mesoamerica.

Archaeological evidence, including murals, codices, and burial offerings reveals that masks were used by priests to invoke deities, channel cosmic forces, and honor the dead.

Many were made from jade, turquoise, or obsidian, carved with exquisite precision and worn by rulers or placed upon the faces of the deceased to ensure safe passage to the afterlife.

Shown above: Jade “Bat God” mask from Monte Albán, Oaxaca, representing the Zapotec god of night and death. Its design symbolizes the duality of decay and rebirth that defined early Mesoamerican spirituality.

Masks were never mere decorations; they were living objects charged with energy, capable of mediating between the mortal and divine worlds.

Colonial Transformation

After the Spanish conquest, masks took on new meanings.

Missionaries recognized their theatrical power and began using them to teach Christian stories through dance and drama, what became known as “danzas de conquista” or “conquest dances.”

Through these performances, Indigenous people reinterpreted Biblical and colonial tales, preserving their own worldview within imposed Christian narratives.

This period gave rise to many hybrid traditions, where European saints, devils, and angels appeared alongside Indigenous gods, warriors, and animals.

Masks became tools of both adaptation and resistance, symbols of cultural survival beneath the veneer of colonization.

Modern Masks and Tourism

By the mid-20th century, Mexico’s folk art began attracting international attention. In the 1950s, art collectors and foreign visitors started purchasing ceremonial masks as decorative objects.

Local artisans began creating pieces specifically for export, experimenting with new materials and colors while preserving traditional forms.

This marked the birth of decorative Mexican masks which were no longer worn in dances but celebrated as works of art.

Today, both ceremonial and decorative masks coexist, the first still danced in rituals and festivals, the second displayed in homes and galleries around the world.

Materials and Craftsmanship

Mexican masks are most commonly made of wood, but depending on the region and purpose, artisans also use clay, stone, leather, papier mâché, coconut shell, or even metal.

The most intricate masks come from regions with strong Indigenous populations, particularly in Guerrero, Michoacán, Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Colima, where ancestral traditions remain vibrant.

Each mask is the result of intimate community knowledge, often passed down from one generation to another.

Crafting a mask involves selecting the right wood (commonly copal, tzompamitl, or avocado), carving by hand, sanding to perfection, then decorating with natural pigments, acrylic paints, hair, lacquer, or animal tusks.

Traditional Masks and Ceremonial Dances

Masks are inseparable from the dances and stories they represent.

Each region of Mexico has its own ritual performances tied to religious festivals, harvest celebrations, or historical events.

The characters: saints, animals, ancestors, or devils, are brought to life through dance, music, and movement.

Below are some of the most iconic examples of traditional Mexican masks, each rooted in centuries of storytelling.

The Pascola Mask

The Pascola, meaning “old man of the feast,” serves as both clown and spiritual mediator during Indigenous celebrations among the Mayo, Yaqui, and Guarijío peoples of northern Mexico.

His dance honors patron saints and is central to Holy Week festivities.

The Pascola wears a carved wooden mask adorned with hair and animal motifs, symbolizing the spirit of the mountains.

He alternates between sacred and comic behavior, dancing solemnly to honor the divine, then joking obscenely to entertain the audience.

When worn on the back of the head, the mask represents humanity. When turned to cover the face, it transforms the dancer into an animal, blurring the line between civilization and instinct.

The Pascola embodies duality, order and chaos, the sacred and the profane in a single figure.

The Devil Mask

Devil masks, or diablos, are among the most widespread in Mexico.

They appear during Christmas “Pastorelas” (shepherd plays), where devils attempt to tempt shepherds on their way to see baby Jesus.

While they represent evil, these devils are mischievous rather than frightening, mixing humor with sin.

Typically carved from wood and painted in bold reds and blacks, they often feature horns, fangs, and long tongues, reflecting both European depictions of Satan and Indigenous ideas of trickster spirits.

These masks are especially popular in Guerrero, Michoacán, and Colima, where entire communities carve them for Carnival and Holy Week dances.

The laughter they provoke serves to neutralize fear, transforming evil into spectacle.

The Giant Mask

In the Danza del Gigante of Chiapas, towering figures reenact the biblical story of David and Goliath.

The dancer playing Goliath wears a large, fearsome mask and carries a wooden machete, charging at the crowd in exaggerated movements that both frighten and amuse children.

This dance combines biblical teaching with festive drama, a theatrical survival of colonial storytelling adapted to local humor.

The Jaguar Mask

The jaguar, a sacred animal since pre-Hispanic times, remains a central figure in Mexican ritual life.

In Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Tabasco, the Danza de los Tecuanes (“Dance of the Beasts”) depicts villagers hunting and killing a jaguar that has attacked their livestock.

In other regions, jaguar dances are performed to ensure rainfall, fertility, and agricultural balance.

Jaguar masks are carved from wood and frequently lacquered. Some are decorated with boar tusks, human hair, and vibrant spots, representing both beauty and danger.

They celebrate the eternal battle between humans and the forces of nature and the respect that must exist between the two.

The Hermit Mask

Used in Pastorela performances, the Hermit Mask portrays a wise pilgrim traveling toward Bethlehem.

Along his path, he encounters devils trying to lure him away from virtue.

Traditionally, men play all roles in these performances, including female and demonic characters, switching masks to embody moral transformation.

The Hermit symbolizes perseverance and faith, reflecting Mexico’s deep syncretism between Indigenous moral codes and Christian allegory.

The Old Man Mask

Among the most beloved Mexican masks is the Old Man or “Viejito” mask, used in the famous Danza de los Viejitos from Michoacán.

The performance begins with stooped, trembling elders barely able to move, their wooden canes tapping the rhythm.

Gradually, the dancers spring to life, dancing energetically in bursts of humor and vitality.

This transformation represents the renewal of life and the cyclical nature of time, the wisdom of age giving way to the joy of youth.

The mask itself, carved with wrinkles and laughter lines, captures the paradox of fragility and endurance.

Animal Masks for the Morenos Dance

In Suchitlán, Colima, the Danza de los Morenos is performed during Easter and Pentecost.

Eighteen dancers, known as Los Morenos, wear brightly colored masks of cats, goats, coyotes, donkeys, roosters, and macaws, dancing in pairs to distract the Roman soldiers guarding Christ’s tomb.

The goal of the performance is to “rescue” Jesus and bring him back to life.

These masks which are lively, colorful, and symbolic combine Indigenous animal totems with Christian narratives of redemption.

The Moors and Christians Dance Masks

The Danza de los Moros y Cristianos arrived in Mexico with the Spanish in the 16th century.

It dramatizes the battle between Christian and Moorish armies, ending with the triumph of Saint James (Santiago).

Though European in origin, Indigenous communities infused it with their own symbolism of conflict, duality, and renewal.

Masks in this dance portray men with beards and elaborate crowns.

In some regions, the Spaniards have light skin and golden hair, while the Moors are dark-faced with black beards which are visual echoes of the conquest narrative reinterpreted through folk art.

Performed in Michoacán, Chiapas, and Estado de México, the dance remains one of Mexico’s most enduring colonial-era performances.

The Conquest Dance Masks

Another dramatization of Mexico’s colonial past, the Danza de la Conquista reenacts the fall of the Aztec Empire.

It features historical figures such as Hernán Cortés, La Malinche, Cuauhtémoc, and the Jaguar Warrior, each represented by a distinct mask.

This dance, performed in Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla, Veracruz, Nayarit, and Jalisco, expresses both trauma and pride, retelling conquest as a story of cultural resistance.

Through masks, Indigenous dancers reclaim agency, portraying heroes and conquerors alike with irony and artistry.

The Pharisees Mask

During Holy Week celebrations across northern Mexico, participants known as Pharisees wear grotesque masks to represent evil forces persecuting Christ.

Made from papier mâché, cloth, or wood, these masks can depict both humans and animals.

At the end of the festivities, they are burned, symbolizing the destruction of sin and the triumph of good.

It is one of the most striking examples of how performance and ritual fuse in Mexican culture, purging negativity through art.

From Ritual to Ornament

The shift from sacred to decorative began in the mid-twentieth century, when foreign travelers and collectors started seeking authentic folk art.

Artisans adapted their ritual masks, refining them for display rather than wear, yet preserving the techniques and iconography that defined their heritage.

Even when detached from the ritual, these masks carry the essence of the dance, humor, duality, and transformation.

They are stories frozen in wood, capturing the spirit of the festivals that gave them life.

Types of Decorative Masks

Decorative Mexican masks often fall into four broad categories, each reflecting a distinct creative tradition: angelic, human, animal, and coconut masks.

Their diversity reflects the same cultural mix that shaped the nation’s ceremonial art, Indigenous mythology, colonial imagery, and local imagination.

1. Angel Masks

Angel masks symbolize divine messengers, most often associated with Catholic pageants such as Pastorelas and Corpus Christi festivals.

When made for decoration, they are painted in soft whites, golds, and blues, sometimes inlaid with mirror fragments or metallic foil.

Their serene expressions represent purity and hope.

In places like Tócuaro and Pátzcuaro, artisans carve these masks from copal or cedar, sanding them smooth and polishing them with beeswax for a warm sheen.

They hang in homes as blessings of protection and light.

2. Human Masks

Human masks portray everyday life and historical figures: farmers, dancers, soldiers, lovers, and saints.

They combine humor and realism, celebrating ordinary people as much as mythical beings.

Some artisans specialize in portraits of village elders or famous dancers, their wrinkles and smiles carefully rendered in wood.

Others interpret colonial characters, such as hacendados, priests, or conquistadors, often with exaggerated features to evoke satire.

These masks reveal how folk artists use irony to reinterpret Mexico’s social past through laughter and caricature.

3. Animal Masks

Animals have been sacred symbols in Mexico since the time of the Olmecs.

Decorative animal masks continue this heritage, representing creatures like jaguars, roosters, coyotes, donkeys, and dogs, each tied to regional myths.

In Guerrero, for example, the lacquered jaguar and devil masks are prized for their deep, glossy finish and vivid colors.

Artisans apply layers of natural lacquer made from chia oil and ground minerals, burnishing each coat until the surface gleams like enamel.

Shown above: Lacquered red devil mask from Tócuaro, Michoacán, a contemporary decorative adaptation of the traditional Diablo mask used in Carnival.

These pieces are rarely identical; each artisan reinterprets the animal’s expression, balancing ferocity and humor.

4. Coconut Masks

One of the most distinctive materials used in Mexican mask-making is the coconut shell, especially along the Pacific coast of Guerrero and Colima.

Artisans carve directly into the shell’s natural curve, using its texture to form faces of jaguars, monkeys, or demons.

The result is lightweight yet striking, half sculpture, half natural object.

The craft of carved coconut masks (máscaras de coco) reached its peak in towns like Suchitlán, Colima, where families continue to make them for local fiestas and for collectors.

Each mask retains traces of the coconut’s fibers, symbolizing the harmony between human craft and natural form

Contemporary Centers of Mask-Making

Despite the rise of modern materials, mask-making in Mexico remains a living folk industry, sustained by families who treat carving as both devotion and livelihood.

Certain towns have become famous for their master artisans and distinctive regional styles.

San Francisco Ozomatlán, Guerrero

The small mountain community of San Francisco Ozomatlán produces some of the most intricately painted devil masks in the country.

Their designs combine colonial Catholic imagery with Indigenous fertility symbols.

Each mask is lacquered with bold yellows, reds, and greens, and decorated with tiny horned creatures or floral motifs that represent the abundance of life.

Artisans here often trace their lineage to generations of dancers who once performed with their own creations.

The mask’s dual purpose, an object of worship and object of art remains central to their identity.

Tócuaro, Michoacán

In Tócuaro, near Lake Pátzcuaro, mask-making is an everyday craft.

Families carve both ceremonial masks for Carnival and decorative versions for collectors.

The most famous are the Diablo masks, painted red and black, often adorned with goat horns and human hair.

The artistry of Tócuaro masks lies in their realistic faces full of teeth and laughter, eyes polished with glass, and features carved so dynamically they seem to move.

These masks embody the playfulness of Michoacán’s festivals, where devils dance among the crowd to mock fear itself.

Shown above: Hand-carved Tócuaro devil mask with multiple horns, painted in lacquer red and accented in gold leaf.

Suchitlán, Colima

In Suchitlán, the mask tradition dates back to pre-Hispanic rituals that honored animal spirits.

The town is now best known for the Danza de los Morenos, where dancers wear colorful animal masks to distract Roman soldiers during Holy Week.

Outside the festival, artisans craft decorative masks featuring roosters, cats, jaguars, and goats, using bright enamels and expressive carving.

Suchitlán masks are recognizable by their wide smiles and high-arched brows, echoing the town’s cheerful and mischievous spirit.

Modern artisans like Herminio Candelario have gained recognition for keeping this tradition alive while adapting designs for contemporary collectors.

Other Notable Centers

- Chilapa, Guerrero: Known for large, elaborately horned masks used in rain dances honoring the spirit Tláloc.

- Yalálag, Oaxaca: Specializes in minimalist wooden masks representing Zapotec ancestors.

- Pahuatlán, Puebla: Produces papier-mâché masks used in Huehue dances during Carnival.

- San Miguel Tenango, Veracruz: Creates painted clay masks combining Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous motifs.

These centers together form a map of Mexico’s living mask heritage, each adapting to its environment and history while sharing a common root in celebration and faith.

The Artisans Behind the Masks

Behind every mask stands an artist whose work carries both lineage and innovation.

Names like Victor Castro of Tócuaro or Herminio Candelario of Suchitlán are respected not only for their technical mastery but for their role as cultural storytellers.

They carve characters that have danced through centuries: saints, devils, animals, and gods, each reimagined for a new generation.

In rural workshops, carving is often a family affair. Children learn by observing, sanding, and painting before moving on to more complex forms.

These intergenerational bonds ensure that even as styles evolve, the soul of the mask remains unchanged.

The Mask as National Symbol

Beyond their local meanings, masks have become emblematic of Mexico’s artistic identity.

They appear in museums, national festivals, and films that celebrate Mexican culture.

Pixar’s Coco, for example, drew visual inspiration from folk masks and Día de Muertos iconography, capturing the colorful blend of reverence and playfulness that defines Mexican spirituality.

Through such representations, the mask continues to embody life, death, and transformation which are the same forces that inspired it thousands of years ago.

A Timeless Dialogue

Whether danced in a village square or displayed in a gallery, Mexican masks preserve an unbroken dialogue between the sacred and the creative.

They remind us that art is not only to be seen but to be lived, but to be worn, celebrated, and believed in.Every carved smile, every painted fang, every polished feather tells the same enduring story:

that behind every mask lies a face, and behind every face, a myth that refuses to fade.

Leave a Reply