Janitzio is a small island in Lake Pátzcuaro, in the southern state of Michoacán. Its name comes from the Purépecha word Janitsio, meaning “corn hair.” The island’s roughly 1,600 inhabitants belong to the Purépecha ethnic group, one of Mexico’s oldest and most resilient Indigenous communities.

Fishing and tourism sustain daily life here, but every year, Janitzio becomes something more: a sacred stage where the living and the dead meet again under candlelight.

Each autumn, the island hosts one of the most iconic Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico, attracting more than 100,000 visitors from Mexico, the United States, Canada, and Europe. Despite the influx of travelers, the celebration retains its profound spiritual character. For the people of Janitzio, honoring their ancestors is not a performance but a duty of love.

The Days of Preparation

The festivities begin on October 31, when local fishermen take to the lake in wooden canoes to hunt ducks using traditional spears.

These ducks are prepared according to regional recipes, cooked with a rich sauce made from chili peppers known as pato enchilado. Along with pescado blanco, the small white fish native to Lake Pátzcuaro, the dish becomes part of the offerings later placed on family altars for the returning souls.

In the morning of November 1, from seven to ten o’clock, the community holds the Kejtzitakua Zapicheri, or “Wake of the Little Angels.” This ceremony is dedicated to children who have passed away.

Mothers and siblings gather at the cemetery to decorate small graves with flowers, toys, candies, and sweets. They sing and pray softly while fathers wait outside the cemetery walls, watching over their families with quiet reverence.

Later that day, the town organizes a contest to select the three best altars built in memory of those who have died during the year. Each altar is a masterpiece of devotion, layered with marigolds, candles, and photographs, reflecting the unique character of the person remembered.

Throughout the afternoon, the open-air theater of Janitzio fills with laughter and applause as traditional dances take place, including “Los Viejitos” (The Old Men) and “El Pescado Blanco” (The White Fish). These performances weave humor and tradition, reminding everyone that life and death are inseparable parts of the same cycle.

Animecha Kejtziatakua: The Night of the Dead

As the sun sets, the atmosphere transforms.

The Night of the Dead, or Animecha Kejtziatakua in Purépecha, begins when fishermen row out into the dark waters of Lake Pátzcuaro. Their canoes, illuminated by hundreds of candles, glide silently across the lake, creating a glowing procession that looks like a river of stars.

The fishermen raise and lower their butterfly nets, performing a symbolic dance that represents the souls returning to earth. The movement of the nets, resembling butterfly wings, honors the ancient belief that monarch butterflies carry the spirits of the departed.

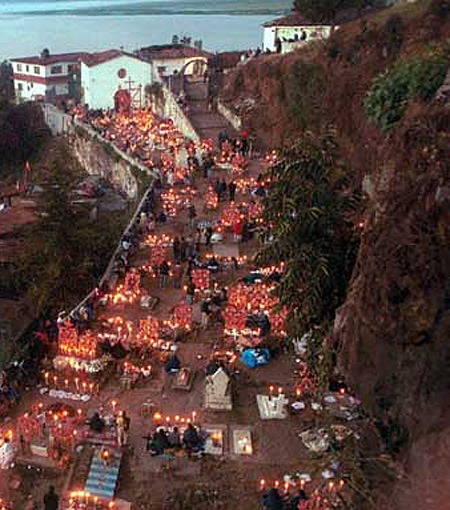

By midnight, the women and children of Janitzio leave their homes, carrying torches, candles, food, and flowers. They make their way to the island’s cemetery, where they prepare offerings to welcome the souls of their ancestors.

The cemetery bell tolls slowly throughout the night, its sound calling the spirits to the land of the living.

By one o’clock in the morning, the cemetery is completely illuminated. Thousands of candles and torches cast a soft glow over graves covered in marigolds, fruit, bread, and incense. The scent of copal fills the air while prayers in Purépecha are whispered into the night.

Women and children keep vigil inside, singing and talking softly to the souls they love. Men remain outside the gates, waiting until dawn, when the vigil ends and the island returns to silence.

Visitors often describe this scene as one of the most beautiful expressions of love in the world, a night where time itself seems to pause, and death is not feared but embraced.

The Legend of Janitzio’s Lovers

Beyond its living traditions, Janitzio holds a legend of love and loss that has become part of its identity.

During the time of the Spanish conquest, Janitzio was part of the Purépecha Empire, ruled by King T’are under Emperor Tzintzicha. When Hernán Cortés sent Cristóbal de Olid to conquer the region, the Spaniards demanded gold and treasures from the empire’s islands in Lake Pátzcuaro.

Emperor Tzintzicha agreed to surrender his riches in exchange for peace and the safety of his people. But some years later, the ruthless conquistador Nuño de Guzmán falsely accused him of treason. Tzintzicha was tortured and executed, igniting an Indigenous rebellion against Spanish rule.

Among those left behind was Mintzita, the emperor’s daughter, who was deeply in love with Itzihuapa, the son of King T’are of Janitzio. The two had planned to marry, but the conquest shattered their hopes.

When Tzintzicha was captured, the lovers offered to exchange a hidden treasure, said to lie at the bottom of Lake Pátzcuaro for the emperor’s freedom.

However, the treasure was guarded by the shadows of twenty drowned boatmen. Itzihuapa bravely dove into the lake to retrieve it, but the spirits pulled him down, making him the twenty-first guardian of the Purépecha riches. Mintzita waited for him on the shore, refusing to leave, until grief claimed her life.

According to the legend, every Night of the Dead, the twenty-one spirits rise from the lake, followed by Mintzita and Itzihuapa. They float toward the island’s cemetery, where the lovers meet once again among the flickering candles. Surrounded by prayers and the scent of marigolds, they whisper to each other while the living honor their own ancestors.

Depicted above: The torture and execution of King Tzintzicha, fragment from the “History of Michoacán” mural by Juan O’Gorman, Pátzcuaro Library.

A Living Heritage

The Day of the Dead in Janitzio is not only a festival but a living form of resistance. It preserves Purépecha beliefs about the continuity of life while blending them with Catholic symbolism introduced centuries ago.

The rituals, dances, and offerings are all expressions of a worldview in which death is part of nature’s eternal rhythm, and love survives beyond it.

To stand on Janitzio’s hilltop cemetery during Animecha Kejtziatakua is to witness one of the most poetic scenes in Mexican culture. The lake glows with candlelight, the air hums with prayers, and the entire island becomes a bridge between two worlds, one of flesh, the other of memory.

In Janitzio, death is not an end but a homecoming.

Leave a Reply