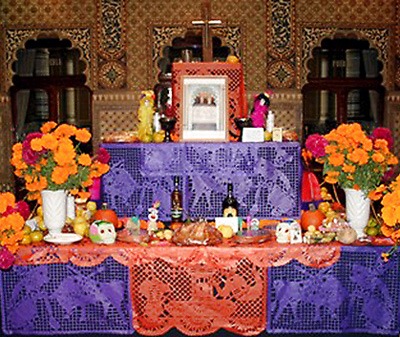

Day of the Dead flowers, or flores de Día de Muertos, are an essential part of Mexico’s annual celebration honoring departed loved ones.

They adorn altars, cemeteries, and streets, filling the air with fragrance and color.

It is believed that the scent of the flowers guides the returning souls to their homes, welcoming them with beauty and joy.

Most of the flowers used for this celebration bloom in the fall, have strong aromas, and carry symbolic meanings related to death, renewal, and remembrance.

Their selection depends on local customs, regional availability, and family tradition.

The Language of Flowers in Día de Muertos

Flowers are considered messengers between the worlds of the living and the dead.

Their short lives mirror the fragility of existence, while their colors express the joy of reunion.

From the golden marigold to the deep red cockscomb, each flower brings its own symbolism and regional flavor to the altar.

Cempasúchil (Tagetes erecta)

The Flower of the Dead

Perhaps the most famous of all, the cempasúchil, or flor de muerto, is native to Mexico and Central America.

Its name comes from the Nahuatl word “cempoalxóchitl,” meaning “twenty flowers.”

The Aztecs used it in religious ceremonies and funerary rituals to honor the sun and the cycle of life and death.

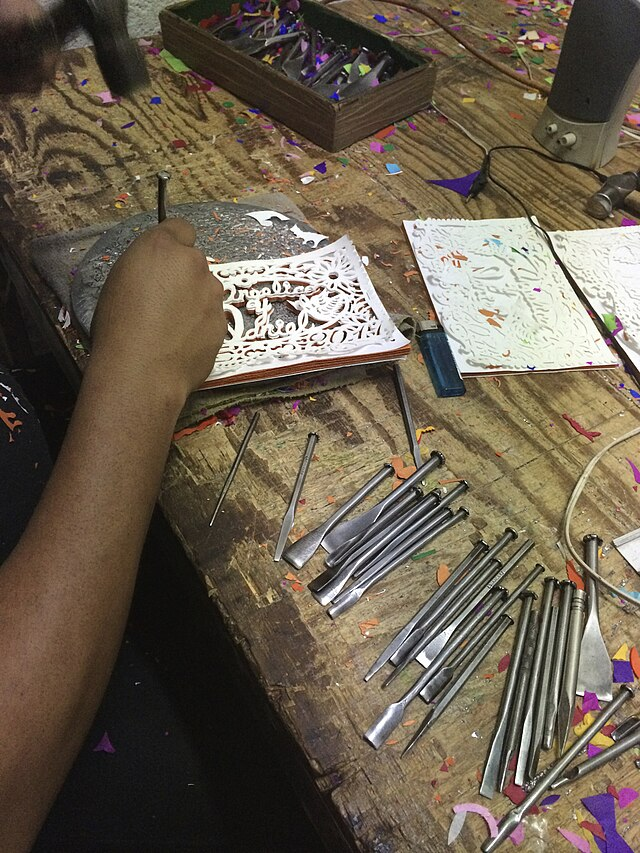

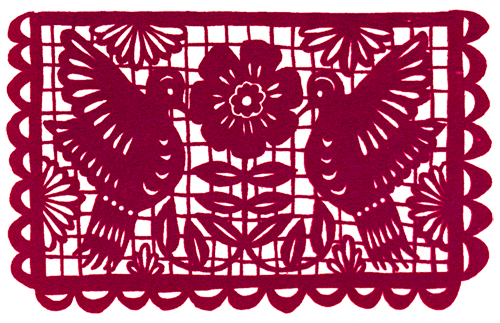

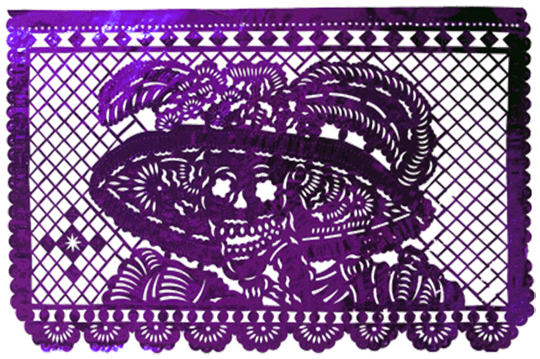

During Day of the Dead celebrations, both natural and paper cempasúchil flowers are used to decorate altars and tombstones.

Families often create arches, crosses, and garlands, and many sprinkle petals on the ground to form a path from the doorway to the altar.

The flower’s bright orange color and strong scent are said to light and perfume the way for the souls returning home.

Terciopelo Rojo (Celosia cristata)

The Velvet Flame

Known in English as red cockscomb, the terciopelo rojo is prized for its vibrant red hue and velvety texture.

The flower can last up to eight weeks and thrives in both humid and dry climates, making it perfect for seasonal decorations.

In Mexican tradition, its red color represents the blood of Christ, symbolizing sacrifice and eternal life.

It is often combined with cempasúchil in altar arrangements, creating a striking contrast of gold and crimson that embodies both death and resurrection.

Alhelí Blanco (Matthiola incana)

The Fragrance of Innocence

The white alhelí, known in English as hoary stock, is cherished for its sweet, delicate scent.

Originally from the Mediterranean region, it symbolizes beauty, purity, and simplicity.

In Mexico, alhelí is especially used on altars for deceased children, where its white color represents the innocence of the young souls returning home.

It is often paired with soft flowers such as baby’s breath to create a tender, peaceful arrangement.

Nube (Gypsophila paniculata)

The Breath of Heaven

Commonly known as baby’s breath, nube is a light, cloudlike flower that complements more vivid blooms.

Native to Europe, it grows best in calcium-rich soils, hence its name derived from gypsum.

In Mexico, nube serves as a filler flower in bouquets and altar arrangements, symbolizing the presence of the divine and the continuity of life.

It is often combined with alhelí, gladiolas, and marigolds to soften the visual texture of the altar and bring balance to the composition.

Crisantemo Blanco (Chrysanthemum morifolium)

A Flower of Farewell

Chrysanthemums, or mums, originated in Asia and were cultivated in China as early as 1500 B.C.

In many cultures, they symbolize grief, remembrance, and the transience of life.

Introduced to Mexico through Spanish influence, white chrysanthemums became common at funerals and All Souls’ Day observances.

Their durable blossoms and calm white tones bring serenity to the vibrant palette of Día de Muertos offerings.

Gladiolas (Genus Gladiolus)

The Flower of Strength and Remembrance

The gladiolus takes its name from the Latin gladius, meaning “sword,” a reference to its tall, pointed leaves.

Native to southern Africa, it symbolizes strength, remembrance, and integrity in many cultures.

In Mexico, gladiolas are arranged in tall bouquets on altars and tombstones, their upright form symbolizing faithfulness and the connection between earth and heaven.

Their elegance and resilience make them one of the most enduring flowers used in Day of the Dead offerings.

A Living Tradition

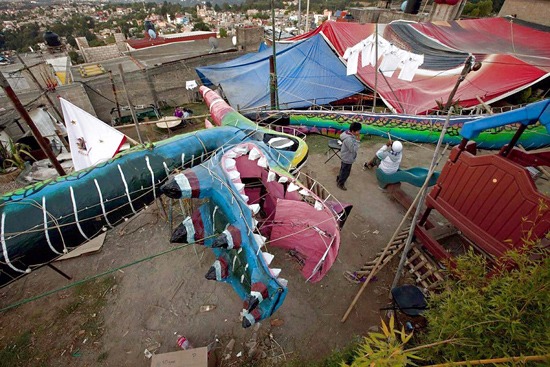

Every year, Mexican flower markets bloom with life as families prepare for the Day of the Dead.

Stalls overflow with mountains of marigolds, bundles of gladiolas, and baskets of alhelí and nube, filling entire neighborhoods with fragrance and color.

The Jamaica Market in Mexico City and the Atlixco Flower Market in Puebla are among the most famous spots to witness this floral spectacle.

Whether freshly cut or made from paper, these flowers remind us that life is fleeting but love is lasting.

Their scent, color, and texture transform grief into celebration, welcoming the spirits home, if only for a night.

Conclusion

Day of the Dead flowers embody the essence of Mexico’s view of death: not as an ending, but as a reunion.

Through petals and fragrance, families express love and remembrance, turning cemeteries and homes into gardens of memory.

Every blossom, from the golden cempasúchil to the pure white chrysanthemum, tells the same story: that life, even in its brevity, is filled with color and meaning.