Long before books, before even paper as we know it, Mexico had its own medium for preserving stories: Amate paper.

Made from the bark of wild fig and mulberry trees, Amate has carried myths, rituals, and memories across centuries.

Today, its surface still holds those same stories, now drawn with ink and color by artists who transform this ancient material into living art.

Origins of Amate Paper

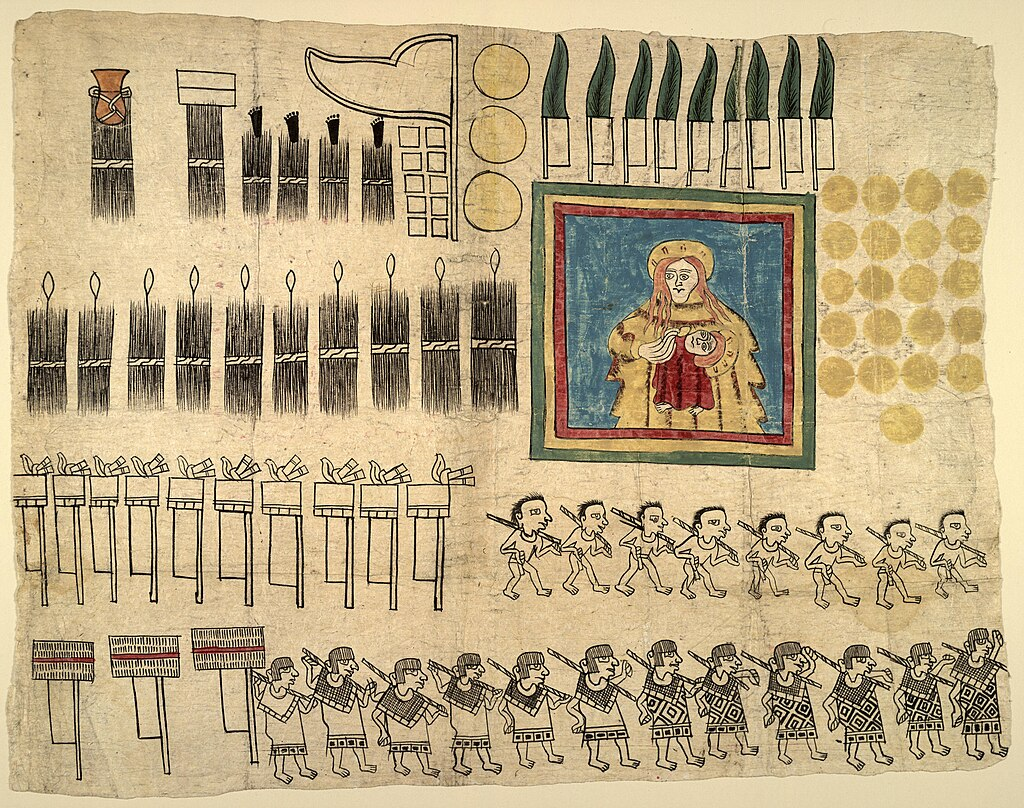

Amate paper dates back to pre-Hispanic times, when it was used by Aztec, Otomí, and Nahua peoples as a sacred writing surface.

Scribes painted on it using natural pigments to record ceremonies, genealogies, and tribute lists at La Mezcala, region of Guerrero. The paper’s name comes from the Nahuatl word amatl, meaning “tree bark.”

For the Aztecs, Amate was not only practical but spiritual.

Priests wrote rituals and prophecies on it, and the paper itself was believed to hold divine energy. It was often burned as an offering to the gods or placed inside temples as part of religious ceremonies.

When the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, they banned its production, fearing its connection to Indigenous religion. But deep in the mountains of Puebla and Hidalgo, the Otomí communities continued making it in secret, preserving the knowledge through generations.

The Revival of Amate Art

Centuries later, in the 1960s, Amate paper reemerged in a new form.

Otomí artisans from San Pablito, Puebla, began selling the paper to Nahua painters from Guerrero, who used it to create intricate paintings of daily life, myths, and festivals.

These artworks (often called Amate paintings) became instantly recognizable for their bold colors, delicate details, and storytelling power.

Scenes of farming, celebrations, births, and dances filled the paper, turning it into a record of community life and imagination.

The white Amate paper, especially, became the preferred canvas for pen and ink drawings that depict entire worlds within a single sheet.

Through fine lines and patterns, artists narrate stories of marriage, harvests, and village legends. Every symbol and gesture carries meaning: the trees, the animals, the arrangement of figures, all speak of balance between people, nature, and spirit.

How Amate Paper Is Made

The process of making Amate paper is an art in itself.

It begins with the bark of the Jonote or Amate tree (species of Ficus and Trema micrantha), harvested sustainably by local artisans.

- Boiling the bark: Strips of bark are boiled for hours with ashes or lime to soften the fibers.

- Pounding: Once soft, they are beaten on a wooden board with volcanic stones until they spread into thin, interwoven layers.

- Sun drying: The sheet is laid flat under the sun to dry, forming a single piece of paper with a rich, fibrous texture.

The result is a surface unlike any other — textured, organic, and warm, with tones that range from creamy white to deep brown depending on the type of bark used.

Each sheet is handmade, so no two are ever alike.

Amate is prized not just for its beauty, but for its resilience. It can last centuries without crumbling, and its irregular texture gives every drawing a tactile, living quality.

The Stories Within the Paper

In many ways, Amate art is a bridge between the ancient codices of pre-Hispanic Mexico and the folk paintings of modern times.

Artists use the same instinct to narrate life: births, weddings, harvests, dances, and dreams, but through a contemporary lens.

The drawings often reflect the collective life of Indigenous communities:

- Farmers tending the milpa (cornfield)

- Women grinding maize or preparing tortillas

- Musicians and dancers during local festivities

- Mythical creatures or nature spirits intertwined with everyday scenes

Even the composition carries meaning. Circles may represent the passage of time, birds symbolize protection, and flowers express joy or abundance.

Each line becomes a voice, and the whole piece — a visual song of community memory.

The White Amate: A Canvas of Precision

While natural brown Amate is often used for colorful paintings, white Amate paper has a special role.

It is preferred for fine pen-and-ink drawings that require precision and contrast.

Artists use black ink, thin brushes, or delicate pens to trace their stories, sometimes filling every inch of the surface with detail.

The whiteness of the paper gives the drawings a luminous, almost spiritual quality — as if the light of the past had been trapped inside the bark.

Many artists describe the act of drawing on Amate as a conversation with the ancestors, each mark awakening something ancient and familiar.

Amate Art Today

Today, Amate art is recognized around the world as one of Mexico’s most distinctive folk traditions.

It has been exhibited in museums, featured in cultural fairs, and collected by art lovers who see in it both craftsmanship and history.

Yet its production still supports small communities.

In San Pablito, entire families participate — men harvest and prepare the bark, women pound and dry the sheets, and children learn to recognize the right texture and thickness.

In Guerrero and Hidalgo, painters work closely with the paper makers, ensuring that this collaboration continues to sustain both traditions.

Buying or displaying an Amate artwork is not just collecting a decorative piece, it is supporting the survival of an Indigenous heritage that has defied centuries of suppression and still speaks with authenticity today.

Where to See Amate Art

If you wish to see Amate art firsthand, the best places are:

- San Pablito, Puebla – home of the Otomí papermakers who preserve the ancient technique.

- Xalitla, Guerrero – known for its vivid Amate paintings of daily life and rural festivities.

- Museo Nacional de Arte Popular (MAP), Mexico City – hosts rotating exhibitions of Amate works from different regions.

- Local craft markets in Oaxaca, Puebla, and Mexico City – where you can meet artisans and purchase authentic pieces directly from them.

The Spirit of the Bark

Amate paper began as a sacred material used for divine communication.

Centuries later, it continues to serve the same purpose — to tell stories, preserve memories, and connect the living with their roots.Each sheet carries the texture of the forest, the rhythm of the hands that made it, and the voice of a people who have never stopped creating.

To hold an Amate drawing is to touch both ancient history and modern imagination, woven together through the bark of a tree and the ink of a storyteller.

Leave a Reply