The Mexican Tree of Life, or Árbol de la Vida, is one of the most iconic symbols in Mexican folk art.

Traditionally depicting the biblical Tree of Life, these hand-coiled clay sculptures once portrayed Adam and Eve with the Serpent.

Over time, however, the art form evolved beyond its religious roots to include themes such as the Day of the Dead, Mexican history, and daily life.

Every tree tells a story, sculpted from clay and painted with the colors of faith, creativity, and joy.

Origins of the Árbol de la Vida

The Tree of Life tradition grew out of the ceremonial clay candelabras and incense burners made in Izúcar de Matamoros, Puebla.

These early pieces were influenced by the bronze and silver religious objects that Spanish friars brought during the colonial era.

Local artisans began replicating them in clay, transforming them into colorful, intricate artworks decorated with flowers, leaves, angels, and animals.

In the center stood Adam, Eve, and the Serpent, with the Archangel Gabriel often placed at the base.

The first potter known to refine this form was Aurelio Flores, who began making his now-famous candelabras in the 1920s.

His detailed, coiled sculptures were not only used in churches but also given to newlyweds as blessings for fertility and prosperity, a symbol of life’s abundance in the farming community of Izúcar.

While this wedding tradition has faded, incense burners remain part of the June 29 celebration of Saints Peter and Paul, the town’s most important religious festival.

No one knows exactly who coined the name Árbol de la Vida.

The earliest known reference dates to 1952, in a book on Mexican folk art by Patricia Fent Ross, which mentioned the clay sculptures of Izúcar by that name.

By the 1970s, the name had spread to describe similar works from Acatlán, Puebla and Metepec, Estado de México, as more artisans adopted the form and expanded its storytelling potential.

Evolution of Meaning and Themes

As collectors and tourists began to appreciate these sculptures, artists moved beyond biblical scenes.

The Tree of Life became a narrative art form, used to tell stories about religion, history, and Mexican culture.

Common subjects include:

- The Creation and Nativity scenes

- The Day of the Dead

- Regional traditions and crafts

- Mexican independence and identity

Each tree became a miniature world and a clay forest filled with symbolism, where birds represent renewal, flowers express fertility, and spiraling branches mirror the cycle of life.

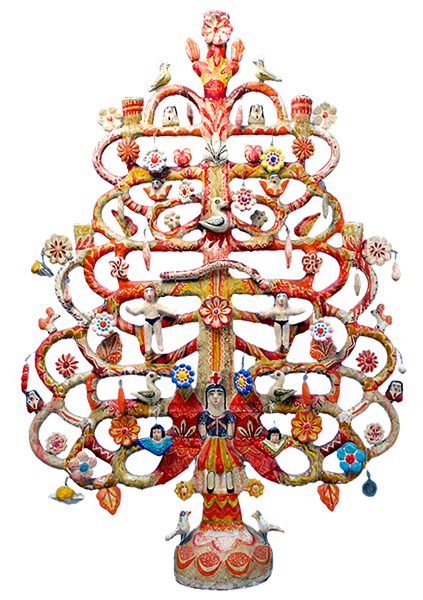

Trees from Izúcar de Matamoros

In Izúcar, Trees of Life still resemble their earliest forms as candelabras and incense burners, painted in vibrant colors and adorned with fine, decorative lines.

They range from small pieces just 10 centimeters tall to monumental sculptures over 2 meters high.

For decades, Aurelio Flores was the town’s most influential artist. His style, passed to his son Francisco Flores, remains the most traditional.

In the 1960s, the Castillo Orta family brought new innovation to the craft.

Their designs introduced fine linear decorations resembling filigree and expanded themes to include the Day of the Dead.

Among them, Alfonso Castillo Orta became internationally renowned, giving Izúcar’s multicolored pottery worldwide fame through his expressive and detailed Trees of Life.

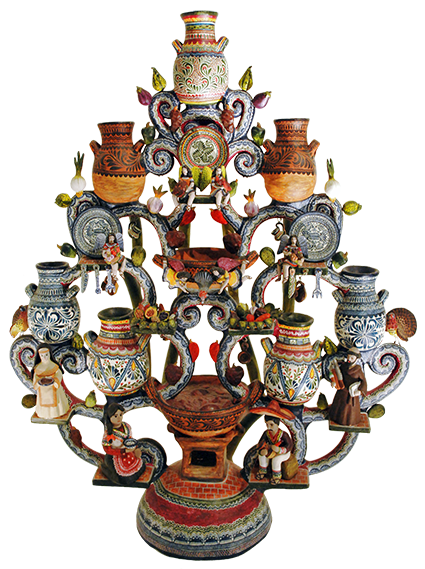

Trees from Acatlán, Puebla

In nearby Acatlán, another master emerged: Herón Martínez Mendoza (1918–1990).

He began by sculpting pieces similar to those from Izúcar but soon developed a style all his own.

His Trees of Life often featured animals, mermaids, or human figures as their base.

He preferred a burnished clay finish, using natural tones instead of bright paint, and incorporated abundant floral and leaf motifs.

Herón’s subjects included the Virgin of Guadalupe, Adam and Eve, Nativity scenes, and even circus figures.

Some of his most ambitious pieces were double-sided, allowing the viewer to explore an entire story around the sculpture.

His work deeply influenced the Acatlán pottery tradition, inspiring artists like Pedro Martínez López, who continues creating beautiful burnished Trees of Life today.

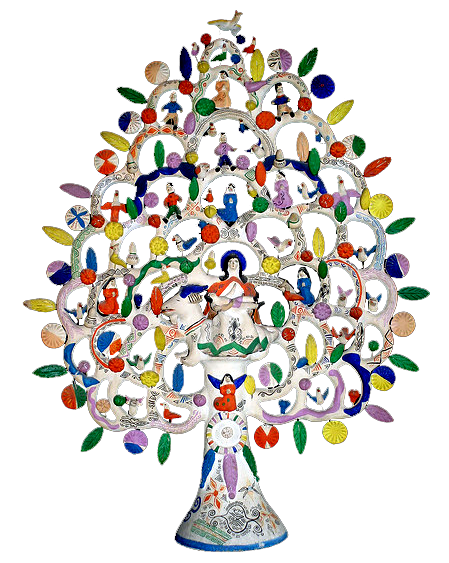

Trees from Metepec, Estado de México

The town of Metepec, near Toluca, has one of Mexico’s richest pottery traditions.

Though it began with utilitarian wares, the art form transformed in the 1940s, when Modesta Fernández Mata experimented with decorative pieces that would evolve into Metepec’s signature Árboles de la Vida.

Together with her husband Darío Soteno León, Modesta raised a family of potters (ten children in all) each one an artist in their own right.

Among the most recognized are Tiburcio Soteno Fernández, their son, and Oscar Soteno Elías, their grandson.

The Soteno family has given Metepec international prestige. Their Trees of Life are known for their refined detail, harmonious colors, and imaginative compositions.

Some are left unpainted, highlighting the natural tone of the clay, while others burst with vivid hues.

They can take the form of candelabras or elaborate altarpieces, ranging in size from tiny figurines to monumental sculptures over five meters tall.

Each Soteno tree is a one-of-a-kind commission, made to order for collectors and cultural institutions worldwide.

Themes span the Day of the Dead, Nativity scenes, Mexican history, and the Virgin of Guadalupe, making every piece a personal and cultural statement.

The Living Legacy of Clay

Across Mexico, the Tree of Life remains one of the country’s most admired and symbolic art forms.

Each town has given it a unique voice, from Izúcar’s joyful color to Acatlán’s earthy elegance and Metepec’s sculptural sophistication.

What unites them all is the belief that clay is alive, that within it lies the power to tell stories, preserve faith, and celebrate creation itself.The Tree of Life is not only a work of art but also a bridge between the sacred and the everyday, between the ancestral and the modern.

Whether standing on an altar, in a museum, or on a collector’s table, it reminds us of Mexico’s enduring creativity, where even earth and fire can blossom into storytelling.

Leave a Reply