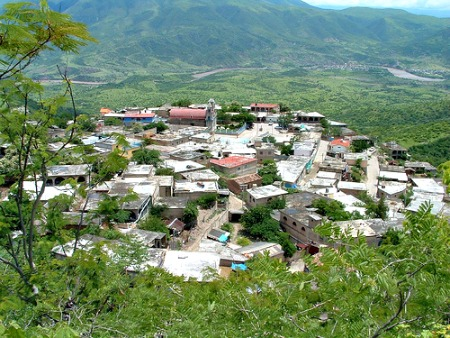

Cristino Flores Medina (1937–2007) was born in Ameyaltepec, a small village in the La Mezcala region on the banks of the Balsas River in Guerrero, Mexico. The area is home to Náhuatl-speaking communities whose language, traditions, and worldview have endured for centuries.

From this fertile land and cultural depth emerged one of Mexico’s most beloved folk artists, a man who transformed daily life into timeless images.

Roots and Beginnings

Ameyaltepec, like its neighboring villages, has practiced pottery since pre-Hispanic times. Over the years, that pottery evolved into what is now known as the painted clay of the Balsas style which are colorful, narrative, and distinctly local.

Shown Above: The village of Ameyaltepec

In these villages, art was a family endeavor. Every household participated: some shaped clay, others painted, and children learned by watching their elders. Cristino grew up surrounded by brushes, colors, and stories. From an early age, he joined in the family craft, painting scenes inspired by the rhythms of his community like the fields, the river, and the celebrations that gave life its meaning.

In 1962, a chance encounter changed everything. His neighbor Pedro de Jesús invited him to Mexico City, where they worked painting wooden figurines in the patio of Max Kerlow’s gallery.

There, they met Felipe Ehrenberg, an innovative Mexican artist who recognized the cultural value in their work.

Ehrenberg encouraged them to experiment with a material both ancient and alive: Amate paper, still made in San Pablito Pahuatlán, Puebla, the same type of bark paper used by Mesoamerican civilizations for codices and rituals.

A New Artistic Language

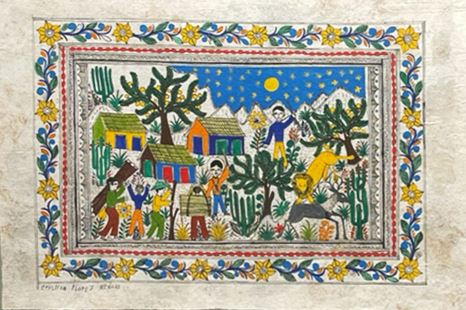

Cristino and Pedro became pioneers of a new folk art movement: painting daily life on amate instead of clay or wood. When they returned to Ameyaltepec, they shared what they had learned, inspiring an entire region. Soon, villages along the Balsas River were filled with amate paintings, each one a fragment of collective memory.

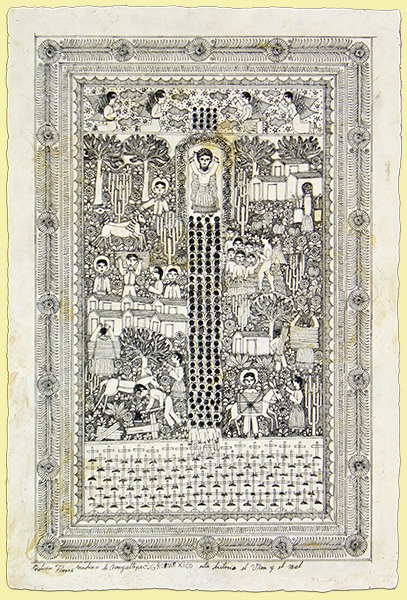

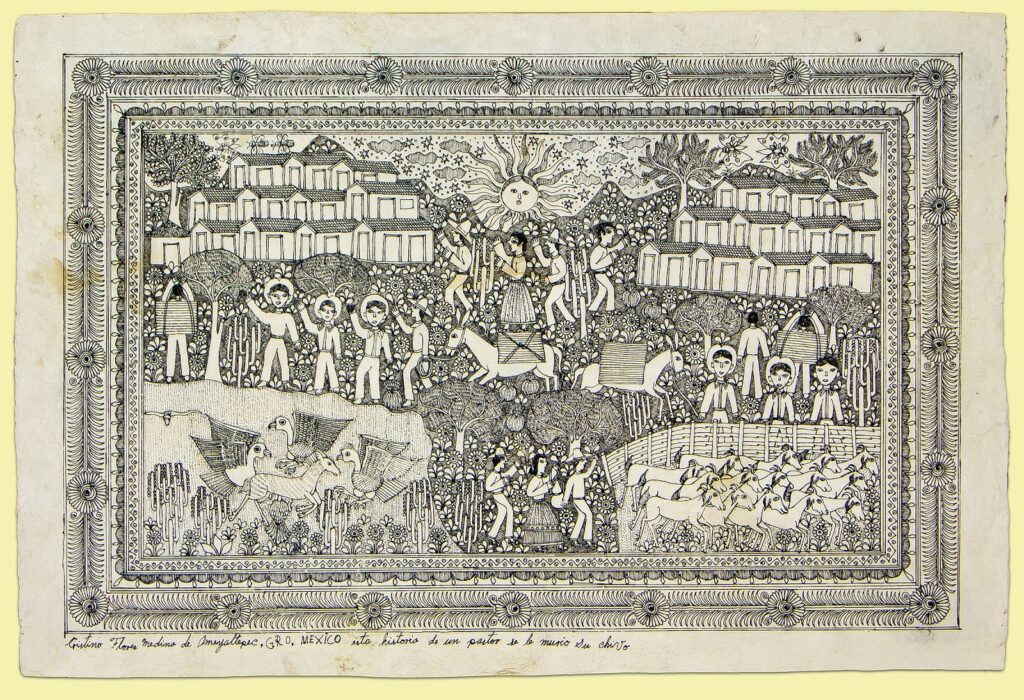

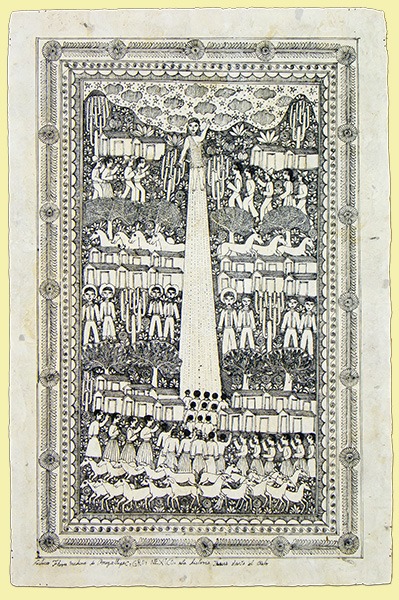

At first, Cristino used bright acrylics, creating vivid depictions of village life. Over time, however, his art evolved toward greater simplicity and precision. He replaced color with India ink and a simple fountain pen, developing a style both humble and profound.

With ink on rough paper, he recorded what he knew best: his people and their way of life.

He drew the maize harvest, deer hunts, fishing traps in the Balsas River, and wood chopping trips with his sons. He captured weddings, funerals, rodeos, patron saint celebrations, and fireworks displays, turning the rhythm of rural Guerrero into visual poetry.

Each drawing was a document of memory, not copied or rehearsed, but imagined from lived experience.

In this way, Cristino became a chronicler of the Nahua world, revealing how his people worked, prayed, celebrated, and dreamed.

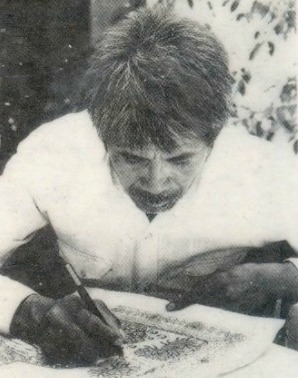

The Artist and His Process

Despite his growing fame, Cristino remained deeply rooted in his land. He worked the fields daily and painted only when the agricultural calendar allowed it. Twice a year, after the harvest, he would travel to sell his work, modestly carrying a portfolio of drawings made during months of patient labor.

Each piece required many hours of delicate linework. Though his subjects often repeated like crops, rituals, community gatherings we could see that no two drawings were ever alike. He drew entirely from memory, guided by the same discipline he applied to his crops.

The Balsas Folk Art Style

Cristino’s paintings embody all the traits of Balsas River folk art:

- Freshness and spontaneity born of direct observation.

- Simplicity and imagination that make his work approachable and universal.

- Lack of formal perspective, giving each piece its characteristic flat, two-dimensional composition.

- Fine and delicate linework that balances the drawn and blank spaces with a master’s instinct.

His art is often described as naïve, but that simplicity hides deep observation and structure. Cristino’s sense of composition and rhythm gives each drawing both movement and stillness, order and emotion.

Those who knew him described him as meticulous, generous, and honest, sparing no effort to make each work reflect truth and dignity.

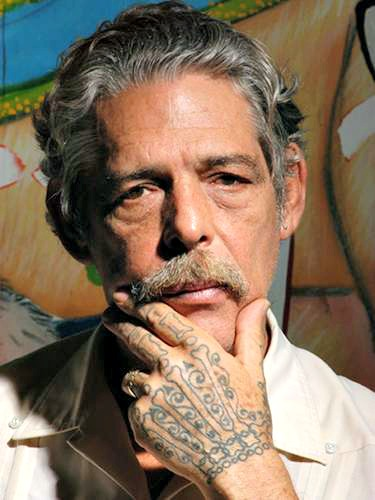

Recognition and Legacy

By the 1970s, Cristino Flores Medina was recognized throughout Mexico as a leading figure in folk painting. His works appeared in exhibitions and collections that introduced the Balsas style to national audiences.

By the time of his passing in 2007, he was internationally acclaimed as one of the founders of Nahua painting on Amate paper, an artist who bridged ancestral technique with modern storytelling.

Cristino’s legacy continues through his children: Crecencio, Andrés, and Juanita Flores who learned to paint at home, just as he did. They proudly continue the family tradition, painting scenes of daily life on Amate and clay, ensuring that the voices of their people remain visible to the world.

Through Cristino’s lines and stories, one glimpses not only the life of Ameyaltepec but the spirit of an entire culture: humble, enduring, and radiant with imagination.

Leave a Reply